José “Pichón” Vargas spent four weeks perfecting a Mexican sandwich he’d never heard of until a cable guy asked for it. Not a torta. Those he knew. The customer wanted layers. Start with tortilla, add beans, add cheese, add meat. Repeat. “Like a Mexican lasagna?” Pichón asked. The cable guy nodded.

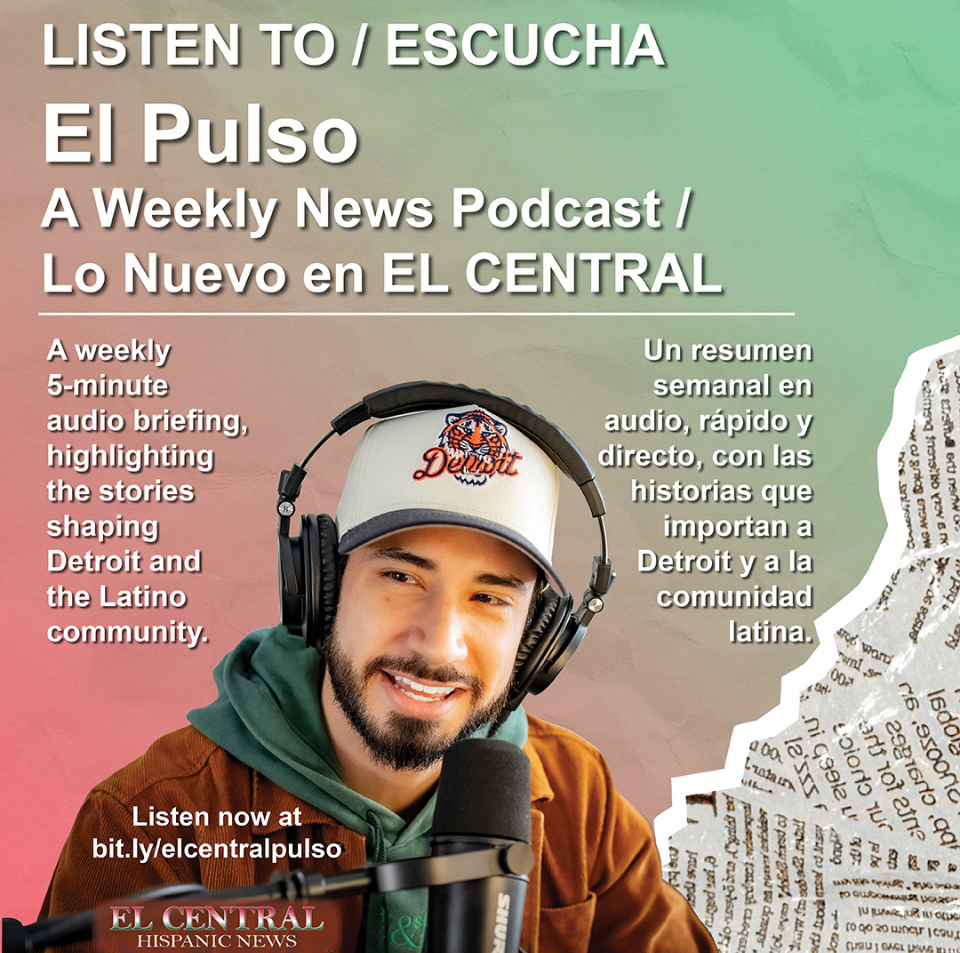

“La Jali” opened its Taylor location on Friday, November 8, at 9411 Telegraph Road (between Wick and Goddard Roads), weeks after that cable guy conversation. Colorful papel picado decorates the ceiling, and the menu runs from traditional Jalisco dishes like birria, sopes, huaraches, quesabirria, and yes, even Tex-Mex.

At the family’s Southwest Detroit restaurant, the 25-year-old executive chef built his reputation by refusing Tex-Mex entirely. But Taylor wanted enchiladas and that sandwich thing. Taylor, five minutes from where the Vargas family lives but worlds away from the Southwest customer base that kept them busy for four years, wanted something familiar. So he adapted.

“In Detroit, I was like, ‘I will never change my menu to Tex-Mex,’” Pichón says. “When I moved here I was like, ‘I need Tex-Mex. There’s no way we’re going to survive if we don’t aim at that market.’”

The well-attended opening drew Taylor Mayor Tim Wooley, who participated in the ribbon-cutting ceremony, and representatives from the Mexican Consulate in Detroit, including Consul Roberto Nicolas Vazquez and Cultural Attaché Marlon Lara Porras.

The Vargas family hadn’t planned to expand. Owner and patriarch José Manuel Vargas bought what his daughter Leslie calls “a sad little market” in Southwest around 2016, after spending a year in the States telling everyone he was done with business. He had run markets in Mexico for 27 years, establishing himself in Mexico City before extortion pushed him out toward his roots in San Ignacio, Jalisco.

The Detroit restaurant needed complete overhaul. José Manuel knew how to turn around failing businesses, his wife Tere could cook, and Pichón had just finished culinary school at Schoolcraft College, where he learned French techniques from master chefs. The family rebuilt the menu, the operations, and the whole business.

“We kind of complement each other really well,” Leslie says. She’s 23, finishing her bachelor’s in Human Resources at Wayne State University while managing operations. “But it’s hard. The business aspect of running a family business is tough.”

Four years in, they had something real. Juan, 20, was handling social media and running the market in Southwest Detroit, sourcing Mexican candies and breads people couldn’t find anywhere else. People came in and cried seeing products they hadn’t seen in 18 years.

Then the previous owner of Pancho’s on Telegraph Road called José Manuel. He was ready to retire and had a building for sale, which was five minutes from José Manuel’s house and already set up as a Mexican restaurant. They bought it in late 2023 and spent a year and a half on permits, construction, equipment, and staff. They signed the papers and started tearing walls down before Taylor Police Department announced full cooperation with Border Patrol in May.

“When that announcement came out, we were already deep in this process,” Leslie says. It was too late to back out, and they’d invested too much. “As a business, you have to learn, adapt, and overcome those challenges.”

Chef Pichón grew up working every station in his family’s businesses. Right after high school he enrolled at Schoolcraft, where they’ve got five Certified Master Chefs on staff. He was 18 and trying to train line cooks twice his age. “That’s serious,” he says. “I needed to learn more.”

The menu at La Jali pulls from Mexico City, Jalisco, and Puebla. “Traditional and adventurous” is how Pichon describes his cuisine. “There are dishes where I like to adventure… give them a twist.”

The family lives in Taylor, but they never really grew up there because they spent all their time at the Detroit restaurant. “You can know an area, but not be part of it,” Leslie says. “That’s something you have to slowly build.”

Detroit customers ordered sopes without asking what they were. Taylor customers wanted enchiladas. Some people recognize La Jalisciense from their reputation in Southwest while others stumble in off Telegraph Road and realize halfway through their meal they’re eating something they couldn’t get anywhere else nearby.

Juan Vargas sees the mercado side in Southwest operating differently than the restaurant. Since the Border Patrol cooperation announcement and federal enforcement ramped up, people stopped coming out. “We survived COVID only because we were a grocery store, a first-need business,” Juan says. “But now people aren’t even going out for basic needs, and that’s scary.”

Kids come in to buy things their parents used to get. “You ask, ‘Where’s your dad?’ and they say, ‘He’s home. He hasn’t left in three months.’”

Pichón splits time between locations while training Taylor cooks and keeping the Southwest location running. Leslie manages both as operations manager while finishing college. Even 11-year-old Nico contributes however he can. During the years it’s taken to open the restaurant, Nico says, “We used all our force for everything here, and now it’s paying off, so it feels nice.”

José Manuel has opened and turned around multiple businesses across three decades, two countries, and five cities. He knows the math: restaurant margins are thin, and doubling locations doubles overhead without guaranteeing doubled revenue. “It’s very hard work, honest work, but it demands total dedication,” he says.

“We never thought La Jalisciense in Detroit would become what it is now,” Leslie says. Now the family is bringing that success home to Taylor, running two kitchens and earning a new community’s trust. After four years of Taylor residents driving to Detroit for their food, the Vargas family is finally cooking in their own backyard.

This article and photos were made possible thanks to a generous grant to EL CENTRAL Hispanic News by Press Forward, the national movement to strengthen communities by reinvigorating local news. Learn more at www.pressforward.news.

Para Ganarse a Taylor, La Jalisciense Agregó Tex-Mex a Su Menú

José “Pichón” Vargas pasó cuatro semanas perfeccionando un emparedado mexicano que nunca había escuchado nombrar… hasta que un técnico del cable se lo pidió. No era una torta. Esas sí las conocía. El cliente quería algo por capas. Empezar con tortilla, luego frijoles, luego queso, luego carne. Y repetir. “¿Como una lasaña mexicana?”, preguntó Pichón. El técnico asintió.

“La Jali” abrió su nuevo local en Taylor el viernes 8 de noviembre, en el 9411 de Telegraph Road (entre Wick y Goddard Roads), apenas unas semanas después de aquella conversación con el técnico del cable. Del techo cuelga papel picado de colores, y el menú va desde platillos tradicionales de Jalisco como la birria, los sopes, los huaraches, la quesabirria, y sí, hasta algo de Tex-Mex.

En el restaurante familiar de Southwest Detroit, el chef ejecutivo de 25 años se había hecho de nombre rechazando por completo la comida Tex-Mex. Pero Taylor pedía enchiladas… y ese “emparedado raro.” Taylor, a solo cinco minutos de donde vive la familia Vargas pero a mundos de distancia del público que los sostuvo durante cuatro años, pedía algo más familiar. Así que se adaptaron.

“En Detroit yo decía: ‘jamás voy a cambiar mi menú por Tex-Mex,’” cuenta Pichón. “Pero cuando me mudé acá, dije: ‘necesitamos Tex-Mex. No hay manera de sobrevivir si no apuntamos a ese mercado.’”

La inauguración, que tuvo gran asistencia, contó con la presencia del alcalde de Taylor, Tim Wooley, quien participó en el corte de listón, y con representantes del Consulado de México en Detroit, incluyendo al cónsul Roberto Nicolás Vázquez y al agregado cultural Marlon Lara Porras.

La familia Vargas no tenía planeado expandirse. El dueño y patriarca, José Manuel Vargas, compró lo que su hija Leslie llama “un mercadito triste” en Southwest alrededor de 2016, después de pasar un año en Estados Unidos diciendo que ya estaba cansado de los negocios. Había manejado mercados en México durante 27 años, estableciéndose primero en la Ciudad de México antes de que la extorsión lo obligara a regresar hacia sus raíces en San Ignacio, Jalisco.

El restaurante de Detroit necesitaba una renovación total. José Manuel sabía cómo levantar negocios en crisis, su esposa Tere sabía cocinar, y Pichón acababa de graduarse de Schoolcraft College, donde aprendió técnicas francesas con chefs de alto nivel. La familia reconstruyó el menú, la operación y todo el negocio desde cero.

“Nos complementamos muy bien,” dice Leslie. Tiene 23 años, está terminando la licenciatura en Recursos Humanos en Wayne State University mientras dirige la parte operativa. “Pero sí es difícil. La parte empresarial dentro de una familia siempre es dura.”

Cuatro años después, ya tenían algo firme. Juan, de 20 años, se encargaba de las redes sociales y del mercado en Southwest Detroit, trayendo dulces y panes mexicanos que la gente no encontraba en ningún otro lado. Más de uno entraba y lloraba al ver productos que no veía desde hacía 18 años.

Entonces el antiguo dueño de Pancho’s, en Telegraph Road, llamó a José Manuel. Estaba listo para jubilarse y tenía un local a la venta —a solo cinco minutos de su casa y ya equipado como restaurante mexicano. Compraron el lugar a finales de 2023 y pasaron año y medio entre permisos, construcción, equipo y contratación de personal. Firmaron los papeles y comenzaron a tirar paredes justo antes de que el Departamento de Policía de Taylor anunciara su cooperación total con Border Patrol en mayo.

“Cuando salió ese anuncio, ya estábamos bien metidos en todo esto,” recuerda Leslie. Era demasiado tarde para echarse atrás, y ya habían invertido mucho. “Como negocio, tienes que aprender, adaptarte y superar esos retos.”

El chef Pichón creció trabajando en todos los puestos de los negocios familiares. Apenas salió de la preparatoria, se inscribió en Schoolcraft, donde tienen cinco chefs certificados a nivel maestro. Tenía 18 años y ya estaba entrenando a cocineros con el doble de su edad. “Era algo serio,” dice. “Necesitaba aprender más.”

El menú de La Jali combina influencias de la Ciudad de México, Jalisco y Puebla. “Tradicional y aventurera,” así describe Pichón su cocina. “Hay platillos donde me gusta experimentar… darles un giro distinto.”

La familia vive en Taylor, pero en realidad nunca creció ahí porque pasaban todo su tiempo en el restaurante de Detroit. “Puedes conocer un área, pero no ser parte de ella,” dice Leslie. “Eso se construye poco a poco.”

Los clientes de Detroit pedían sopes sin tener que preguntar qué eran. Los de Taylor buscan enchiladas. Algunos reconocen La Jalisciense por su reputación en Southwest, mientras otros entran por casualidad desde Telegraph Road y, a mitad de su comida, se dan cuenta de que están comiendo algo que no encontrarían en ningún otro lugar cercano.

Juan Vargas nota que la parte del mercado en Southwest funciona distinto al restaurante. Desde el anuncio de cooperación con Border Patrol y el aumento de la presencia federal, la gente ha dejado de salir. “Sobrevivimos al COVID solo porque éramos una tienda de primera necesidad,” dice Juan. “Pero ahora ni para lo básico están saliendo, y eso da miedo.”

Los niños todavía entran a comprar los dulces que sus papás compraban antes. “Les preguntas: ‘¿y tu papá?’ y te dicen: ‘Está en casa. No ha salido en tres meses.’”

Pichón divide su tiempo entre las dos ubicaciones, entrenando al personal en Taylor y manteniendo a Southwest en marcha. Leslie maneja ambas como encargada de operaciones mientras termina la universidad. Incluso Nico, de 11 años, ayuda en lo que puede. Durante los años que ha tomado abrir el restaurante, Nico dice: “Usamos toda nuestra fuerza para lograrlo, y ahora que se ve el resultado, se siente bonito.”

José Manuel ha abierto y rescatado varios negocios a lo largo de tres décadas, dos países y cinco ciudades. Sabe bien que los márgenes en la restauración son delgados y que duplicar locales también duplica los gastos sin asegurar el doble de ganancias. “Es trabajo muy duro, honesto, pero exige dedicación total,” dice.

“Nunca pensamos que La Jalisciense en Detroit se convertiría en lo que es ahora,” agrega Leslie. Ahora la familia lleva ese éxito a Taylor, manejando dos cocinas y ganándose la confianza de una nueva comunidad. Después de cuatro años en que los residentes de Taylor manejaban hasta Detroit para probar su comida, la familia Vargas por fin está cocinando en su propio vecindario.