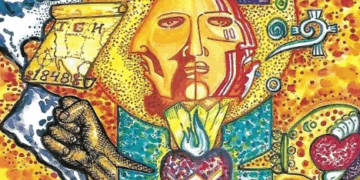

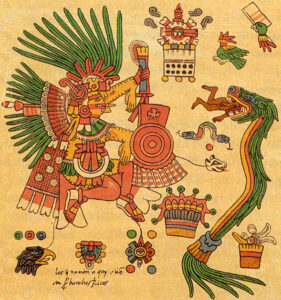

En una época en que el mundo estaba sumergido en las tinieblas, los dioses se reunieron en Teotihuacan y se preguntaron quién iba a tomar a su cargo la tarea de iluminar al mundo. El rico y presuntuoso Tecciztécatl declaró: “Yo lo haré.” Pero era necesario otro candidato. Los dioses designaron entonces, tal vez para burlarse, al pobre de Nanahuatzin, que padecía una grave enfermedad de la piel, pero que aceptó.

Mientras los dioses encendían un gran fuego en un “horno divino”, cada uno de los dos héroes se retiró a la cúspide de una pirámide para consagrarse durante cuatro días al ascetismo y a la realización de ciertos ritos. Las ofrendas del primero eran fastuosas, las del segundo risibles. Pero mientras que el primero ofrecía falsas espinas de coral rojo, el segundo ofrecía verdaderas espinas entintadas con su propia sangre. Antes de la prueba final, cada uno se preparó según sus medios, el primero con pompa y el segundo miserablemente.

Luego, los dioses se formaron en dos filas, formando una especie de avenida que conducía al brasero divino. Cada candidato debía correr entre las dos filas y lanzarse a las llamas. Tecciztécatl lo intentó en vano en cuatro ocasiones, pero todas las veces le faltó valor. El pobre de Nanahuatzin, más valiente, se lanzó a la primera, ganando así la prueba. Su rival, azuzado por la vergüenza, lo siguió a las llamas, cuyo ardor había disminuido. Un águila y un jaguar se lanzaron tras él, de donde la costumbre de llamar a los guerreros valientes “águilas-jaguares”.

Vino entonces un largo momento durante el cual los dioses esperaban la primera aurora. Finalmente, el cielo comenzó a clarear por todas partes y los dioses se preguntaron en qué dirección saldría el sol. Quetzalcóatl, Tótec y los innumerables Mimixcoa, así como cuatro diosas fueron los pocos que adivinaron que saldría por el este.

Al fin, Nanauatzin, convertido en el sol, apareció resplandeciente. Pronto le siguió Tecciztécatl, convertido en la luna. Los dos astros brillaban casi lo mismo uno que el otro. Los dioses estaban tan sorprendidos que uno de ellos lanzó un conejo a la cara de la luna, que perdió así brillantez.

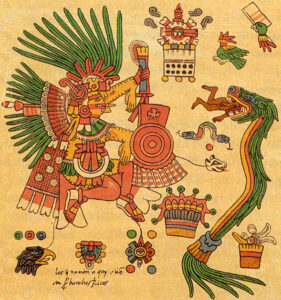

Pero ni el sol ni la luna tenían fuerza para moverse. Los dioses decidieron entonces que era preferible dar su vida para animar al sol que vivir miserablemente entre el pueblo común. Ehécatl, el viento, se encargó de sacrificarlos, uno tras otro. El último fue Xólotl, quien, para tratar de escapar a la muerte, se transformó inútilmente en un tallo de maíz doble llamado xólotl, en un agave doble llamado mexólotl y en un batracio llamado axólotl.

Una vez muertos todos los dioses, el sol seguía inmóvil, pero entonces el viento, soplando con violencia, lo forzó a entrar en movimiento. La luna se quedó atrás, y desde entonces ambos astros caminan separadamente.

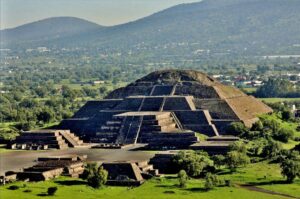

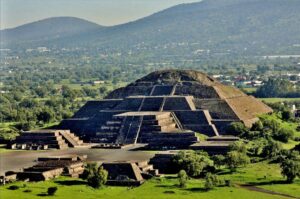

Teotihuacan, cuyo nombre significa “lugar de la apoteosis, se consideraba el sitio por excelencia para la divinización de los muertos. Se trata de un sitio arqueológico grandioso del norte del Valle de México, donde se alzan dos grandes pirámides, que los aztecas del siglo XVI llamaban pirámide del sol y pirámide de la luna. Estos dos monumentos se remontan a los primeros siglos de nuestra era; el sitio estaba abandonado desde hacía 700 años cuando Sahagún recogió esta leyenda. En esa época los constructores de las pirámides habían pasado a formar parte de los mitos y no quedaba de ellos el menor registro histórico. Las ruinas tenían todavía un aura de prestigio, pero sería aventurado afirmar que la leyenda que prevalecía entonces correspondiera al destino previsto por los constructores desaparecidos.

The Creation fof the Aztec Sun

At a time when the world was immersed in darkness, the Aztec gods gathered in Teotihuacan and asked themselves who was going to take on the task of illuminating the world. The rich and presumptuous Tecciztécatl declared: “I will do it.” But another candidate was needed. The gods then appointed, perhaps to mock him, poor Nanahuatzin, who suffered from a serious skin disease, but whom he accepted.

While the Gods lit a great fire in a “divine oven,” each of the two heroes retired to the top of a pyramid to dedicate themselves for four days to asceticism and the performance of certain rites. The offerings of the first were lavish, those of the second laughable. But while the first offered false red coral spines, the second offered real spines inked with his own blood. Before the final test, each one prepared according to his means, the first with pomp and the second miserably.

Then, the gods formed in two rows, forming a kind of avenue leading to the divine brazier. Each candidate had to run between the two rows and throw themselves into the flames. Tecciztécatl tried in vain on four occasions, but each time he lacked courage. The poor man from Nanahuatzin, braver, took the first step, thus winning the test. His rival, spurred on by shame, followed him into the flames, whose ardor had diminished. An eagle and a jaguar rushed after him, hence the custom of calling brave warriors “jaguar-eagles.”

Then came a long moment during which the gods waited for the first dawn. Finally, the sky began to lighten everywhere and the gods wondered in which direction the sun would rise. Quetzalcóatl, Tótec and the countless Mimixcoa, as well as four goddesses were the few who guessed that it would emerge from the east.

At last, Nanauatzin, transformed into the sun, appeared resplendent. Tecciztécatl soon followed, transformed into the moon. The two stars shone almost the same as each other. The gods were so surprised that one of them threw a rabbit in the face of the moon, which thus lost its brilliance.

But neither the sun nor the moon had the strength to move. The gods then decided that it was preferable to give their lives to cheer up the sun than to live miserably among the common people. Ehécatl, the wind, was in charge of sacrificing them, one after another. The last was

Once all the gods were dead, the sun remained motionless, but then the wind, blowing violently, forced it to move. The moon was left behind, and since then both stars have walked separately.

Teotihuacan, whose name means “place of apotheosis,” was considered the site par excellence for the deification of the dead. It is a grandiose archaeological site in the north of the Valley of Mexico, where two large pyramids stand, which the 16th century Aztecs called the pyramid of the sun and the pyramid of the moon. These two monuments date back to the first centuries of our era; The site had been abandoned for 700 years when Sahagún collected this legend. At that time the builders of the pyramids had become part of the myths and not the slightest historical record remained of them. The ruins still had an aura of prestige, but it would be risky to say that the legend that prevailed then corresponded to the destiny foreseen by the missing builders.