En la época prehispánica el culto a la muerte era uno de los elementos básicos de la cultura, cuando alguien moría era enterrado envuelto en un petate y sus familiares organizaban una fiesta con el fin de guiarlo en su recorrido al Mictlán, el mundo de los muertos.

Según una leyenda mexica, quien hubiera tratado mal a un perro no podría atravesar jamás el profundo río Apanohuaia, pues ni Xólotl ni su perro Xoloitzcuintle lo ayudarían a llegar al Mictlán. En su tumbale colocaban comida que le había agradado en su vida, con la creencia de que podría llegar a sentir hambre durante su tránsito.

En la visión indígena el Día de Muertos tenía relevancia porque implicaba el tránsito de las ánimas de los difuntos para regresar a donde había sido su casa en el mundo de los vivos y, así, convivir con los familiares, de ahí la importancia del alimento que se les ofrece en los altares puestos en su honor, como forma de hacerles notar que se les espera, que su presencia es grata.

Su origen se ubica en la armonía entre la celebración de los rituales religiosos católicos traídos por los españoles y la conmemoración del día de muertos que los indígenas realizaban desde los tiempos prehispánicos; los antiguos mexicas, mixtecas, texcocanos, zapotecas, tlaxcaltecas, totonacas y otros pueblos originarios de nuestro país, trasladaron la veneración de sus muertos al calendario cristiano, la cual coincidía con el final del ciclo agrícola del maíz, principal cultivo alimentario del país.

La celebración del Día de Muertos se lleva a cabo los días 1 y 2 de noviembre, ya que ésta se divide en el 1 de noviembre que corresponde al día de Todos los Santos, día dedicado a quienes murieron siendo bebés o niños; el día 2 de noviembre para los Fieles Difuntos, es decir, a los adultos.

Cada año muchas familias colocan ofrendas y altares con la foto de a quien conmemoran y decorando el altar con flores de cempasúchil, papel picado, calaveritas de azúcar, pan de muerto, mole o algún platillo que le gustaba a sus familiares a quien va dedicada la ofrenda, y al igual que en tiempos prehispánicos, se coloca incienso para aromatizar el lugar. Se cree que las ofrendas puestas en el altar convocan la visita desde la tierra de los muertos.

En tiempos más recientes, la gente se reúne en sus ciudades, se disfraza con caras pintadas de Calavera (Esqueletos) y tiene desfiles en las calles.

Las visitas al cementerio también son comunes el último día, ya que las familias van a decorar las tumbas con flores de caléndula, regalos y calaveras de azúcar con el nombre del difunto. Es costumbre limpiar la lápida y restaurar los colores de la tumba.

El altar u ofrenda, según dicta la tradición, puede llevar desde tres niveles sin contar el suelo, siete niveles, algunos incluso hacen de trece niveles como los trece mundos del Mictlán. Es importante destacar que esta tradición contemporánea es un resultado del mestizaje entre las creencias de los mitos indígenas y el catolicismo español de la colonia.

La festividad a la muerte en México manifiesta la dicha de vivir a través de la gratitud colorida, festiva y llena de tantas expresiones como es posible. Algunas personas cuestionan la vigencia del imaginario de esta tradición que pareciera pertenecer a un tipo de realismo mágico, ya que actualmente la sociedad globalizada poco sostiene la creencia de que los muertos vendrán a compartir el festín; no obstante, los altares y ofrendas en este día sirven para recordarnos a los mexicanos que siempre hay algo y alguien a quien agradecer-celebrar.

Calaveritas literarias

Las calaveritas literarias son poesías populares, retratan la manera animosa y cómica en que el mexicano se mofa y desafía a la Muerte, se burla de amigos, políticos, artistas, etcetera; al fin y al cabo, como dijo el grabador Guadalupe Posada, “la muerte es democrática”, por eso en las calaveras literarias hay verbena para todos.

Mi amiga y muerte

Estaba sentada la muerte

tratando no hacerse notar

mi amiga con mala suerte

a su lado se fue a parar.

La catrina andaba amargada,

mi amiga plática sacó,

la catrina quería que se callara

pero mi amiga no paró.

La catrina muy enojada

a irse de ahí la mandó,

pero ella no la pelaba

y a la pobre le tocó morir.

Abril García Barraza

Day Of The Dead

In pre-Hispanic times, the cult of death was one of the basic elements of the culture. When someone died, they were buried wrapped in a mat, and their relatives would organize a party to guide them on their journey to Mictlán, the world of the dead.

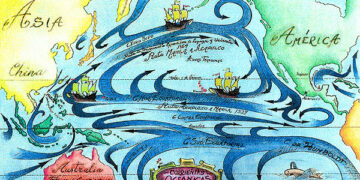

According to a Mexica legend, anyone who mistreated a dog could never cross the deep Apanohuaia River, as neither Xólotl nor his dog Xoloitzcuintle would help them reach Mictlán.

As part of the cult, food that they had enjoyed in their lives was placed in their tomb, with the belief that they might become hungry during their journey.

In the indigenous world, the Day of the Dead was significant because it represented the return journey of the souls to their former home in the world of the living and, thus, to spend time with their relatives. Hence the importance of the food offered to them on the altars set up in their honor, as a way of letting them know that they are expected and that their presence is welcome.

Its origin as a celebration lies in the syncretic harmony between the celebration of Catholic religious rituals brought by the Spanish and the commemoration of the Day of the Dead, which indigenous peoples had practiced since pre-Hispanic times. The ancient Mexica, Mixtec, Texcocan, Zapotec, Tlaxcalan, Totonac, and other indigenous peoples of Mexico, people who transferred the veneration of their dead to the Christian calendar, which coincided with the end of the agricultural cycle of corn, the country’s main food crop.

The Day of the Dead celebration takes place on November 1 and 2, as it is divided into November 1, which corresponds to All Saints’ Day, a day dedicated to those who died as infants or children, and November 2, for All Souls’ Day, that is, adults. Every year, many families place offerings and altars with the photo of the person they commemorate, decorating the altar with marigold flowers, confetti, sugar skulls, pan de muerto (bread of the dead), mole, or a favorite dish of their family member to whom the offering is dedicated. As in pre-Hispanic times, incense is placed to scent the place. It is believed that the offerings placed on the altar summon a visit from the land of the dead.

In more recent times, people gather in their cities, dress up in costumes with painted skull faces, and hold parades in the streets.

Visits to the cemetery are also common on the last day, as families go to decorate the graves with marigold flowers, gifts, and sugar skulls bearing the name of the deceased. It is customary to clean the tombstone and restore the colors.

The altar or offering, according to tradition, can range from three levels, not including the floor, to seven levels, and some even have thirteen levels, like the thirteen worlds of Mictlán. It is important to note that this contemporary tradition is a result of the fusion of indigenous myths and colonial Spanish Catholicism.

The celebration of death in Mexico expresses the joy of living through colorful, festive gratitude, filled with as many expressions as possible. Some people question the validity of this tradition’s imagery, which seems to belong to a type of magical realism, since today’s globalized society has little support for the belief that the dead will come to share the feast. However, the altars and offerings on this day serve to remind Mexicans that there is always something and someone to thank and celebrate.

Traditional Poetry: Calaveritas

Literary Calaveritas are popular poems written in rhyme that portray the spirited and comical way in which Mexicans mock and defy death, poking fun at friends, politicians, artists, and so on. After all, as the engraver Guadalupe Posada said, “death is democratic, it reaches everyone,” which is why there’s something for everyone in literary skulls.

My friend and death

Trying not to be noticed

Death was sitting

my unlucky friend

next to her she went to sit.

The catrina in bad mood

feeling she was,

my talkative friend

couldn’t contain her chatting,

the catrina wanted to shut her up

but my friend did not stop.

The catrina very angry

ask her to leave there,

but my friend didn’t get it

so, the catrina had to take her away.

April Garcia Barraza