Detroit’s underground art scene showed up in force this past Monday night at The Platform in Tech Town with a simple message: fix the broken system. Local artist and rapper Demacio worked quietly in the corner on a live painting while a diverse crowd, ranging from filmmakers to lawyers and small business owners, gathered to talk about what many consider Detroit’s most valuable asset: Its culture.

The event, hosted by Visit Detroit’s Global Underground Ambassador Michael Reyes – who introduced himself first as “Reyes Poetry” and made a point to mention that he was speaking not on behalf of his organization We Are Culture Creators, but as an individual – brought Detroit City Council President Mary Sheffield face-to-face with a small but vocal group of the city’s creative community. Sheffield, who is also running for mayor, arrived slightly under the weather but eager to engage on issues affecting Detroit’s cultural curators.

“As Detroit is going through this kind of, I don’t know, shift in city services and maybe regulation,” Reyes began, “what is your platform on arts and in particular kind of like the underground creative art scene, or maybe the nighttime economy?”

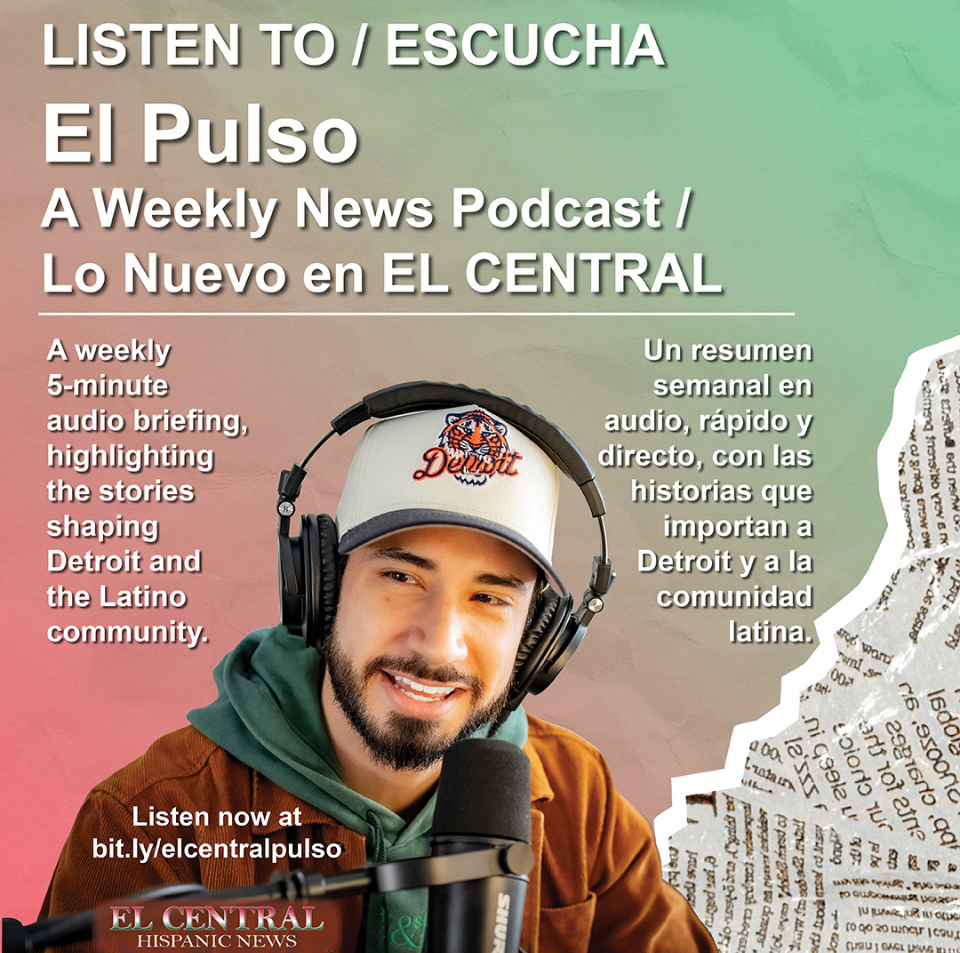

For many in attendance, the answer to that question has significant economic implications. Reyes, who produces “100 events a year” working with “probably 50 different groups,” represents just one node in Detroit’s extensive network of “cultural curators”—a casual term coined to describe the underground event organizers, community builders, and vibe architects of Detroit who represent the frontlines of the city’s creative economy.

“Our biggest export is culture for Detroit,” Reyes stated plainly.

Operating similar to small businesses, culture curators face unique regulatory challenges. When Reyes and his team started a festival seven years ago, they were “underground, for sure.” He acknowledged they “didn’t even understand that there was an events department,” but pointed out the red tape creators must cut through and why many events start underground: “Looking at the regulation that exists, had we started that completely legal, we wouldn’t have been able to scale it.”

Sheffield didn’t shy away from acknowledging the regulatory burden facing all Detroit entrepreneurs.

“It’s extremely difficult, whether you’re talking about zoning, permitting, the city bureaucracy,” Sheffield admitted. “It’s 182 steps just to start a restaurant, six departments, $4,000 in fees—most people just stop and go to the suburbs.”

For event producers, these challenges are compounded by shifting regulations and inconsistent enforcement. Reyes described preparing for a Cinco de Mayo event only to have capacity limits suddenly changed at an event he recently held. “And because we don’t really know [the fire marshal’s rules and regulations], and it’s not in print, we’re kind of left in limbo the day before,” he explained. “And then it’s like, you know, what do we do? Who do we call? Who do we connect with?”

Despite these challenges, no one argued against the need for reasonable oversight. In fact, quite the opposite.

“I think every producer that is a part of our group wants our events to be safe,” Reyes emphasized. The issue, as he framed it, was about consistency and communication: “If we know the rules, we can engage and then we can figure it out.”

Sheffield agreed. “I think there needs to be more communication and coordination,” she said. “The way in which we do special events in Detroit, people need to know at the onset what is expected. How can we better work with events and local artists at putting on events that are safe, and then not creating so many barriers?”

She added firmly: “We don’t want to be a barrier and so burdensome that it’s so hard to do events in Detroit that it prevents local artists and others from actually setting up shop.”

Reyes highlighted disparities in how different events are regulated. “When we see something like the NFL Draft, they’re able to leverage… and you kind of see 750,000 people downtown that are able to just move freely.” In contrast, smaller cultural events face more scrutiny, he noted.

More pointed was his observation about racial disparities in event regulation: “Being somebody who is non-black that works within black spaces and feels privileged to do that, there is a different conversation when we’re bringing up a black-focused event or festival” – a statement Sheffield wholeheartedly agreed with. “We just want the playing field to be equal,” said Reyes.

“Just Shacoi,” who had provided music as the DJ earlier in the evening before joining the crowd as a concerned citizen, raised concerns about major festivals coming to Detroit without involving local talent. “It feels almost unfair and a spit in the face as not only a community of big organizers, but also a DJ, to see these big festivals come in and touch no local artists,” she said. “We have some of the best DJs in the world. I see the techno Godfathers promoted all over Berlin way more than here.”

Throughout the evening, Sheffield offered several concrete solutions to address these challenges.

“First and foremost, we are going to create an Office of Small Business Affairs,” she promised, describing it as providing “the ecosystem that a lot of small businesses don’t have” to navigate city bureaucracy.

She also committed to continuing a dedicated role working with the nightlife economy, similar to the position previously held by Adrian Tonon, Mayor Mike Duggan’s chosen “Nighttime Economy Ambassador.” (A quick search on Tonon’s LinkedIn boasts him as “the first ever Night Time Mayor for the City of Detroit.”)

Sheffield “would love to have someone in the Mayor’s office that’s directly working with the nightlife. Most definitely, that will be something that I will continue.” When asked about supporting existing creative spaces, she referenced a recent win for independent filmmakers: “In the budget for the first time, we put an urge that we create a grant program to give grants to our local, independent film artists.” But whether “an urge” is a line item in the budget remains unclear.

Sheffield did express openness to similar programs for other cultural curators, acknowledging, “I think we have a lot of work to do to ensure that that department is actually working on behalf of our artists here locally in Detroit.”

Chris Scott, Sheffield’s campaign manager, emphasized the importance of arts and culture to Detroit’s future. With a background in performing arts and film production himself, Scott described the arts scene as a “legacy industry” essential to neighborhood revitalization and economic diversification.

“We don’t get our neighborhoods back, we definitely don’t diversify our economy without y’all,” Scott told the gathered creatives.

Sheffield echoed this sentiment in her vision for the city. “My vision is to create a world class city,” she said. “In order to do so, I think we have to have a strong and vibrant and thriving arts and culture scene.”

She acknowledged that while her time on City Council has been “laser focused on issues like housing in Detroit, poverty and basic social services,” she expressed interest in “tapping into a little bit more to see how my office… can better be of assistance to you all.”

Detroit’s cultural curators face a basic problem: how to keep creating while dealing with city rules that make everything harder to pull off. As Sheffield put it, the goal is “ensuring that this is a destination of opportunity, a place where young people feel that there is opportunity here right in our city. They don’t have to go to LA or DC or New York.”

Whether Sheffield and the city’s leadership can deliver on these promises remains to be seen. But this evening, at least, they were listening.