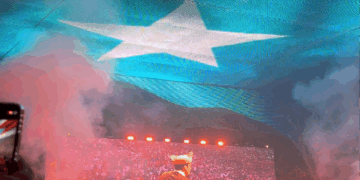

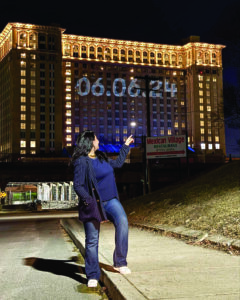

On the evening of February 19, 2024, Detroit’s Michigan Central projected “6/6/24” in blue numbers across the north and south entrances of the 550-foot-wide building. The date, which could be seen from miles away, was set for the grand opening of the five-year, $950 million renovation of the former train station—the most anticipated development project in Detroit in more than fifty years.

For Alondra Alvizo, associate director of community engagement at Michigan Central, having the date of the grand opening projected not only on the north side of the building but on the south side facing Mexicantown was as exciting as it was personal. Michigan Central had projected many things on the building, but always on the side facing Corktown, never on the side facing the Latino community.

“I brought the idea up in a staff meeting,” Alvizo said. “Originally, we were only going to do ‘June 6 on the north [facing Roosevelt Park],’ and I asked if we could project it in Spanish on the south side, but instead we projected 6/6/24 on both sides.” In Southwest

Detroit, people stopped to stare at the projection, the first time the owners of the building had spoken directly to them. Many got out of their cars to take photos. Social media erupted with the news.

Juan Carlos Gutierrez, 28, whose family has called Southwest Detroit home since 1995, happened to be walking outside when he spotted the projection. He said seeing the date displayed brought him a sense of palpable excitement.

“I was happy that both sides of the train station were included in the projection. The Corktown side gets all the publicity, and it feels like our side is forgotten, like it’s in the shadow,” Gutierrez said.

Alvizo grew up in the city’s Mexican community and knew what Michigan Central meant to Southwest Detroiters. The train station has been a towering presence in the heart of a thriving Latino community that for decades watched its slow, painful decline.

As a teen, she remembers driving past Michigan Central daily to attend Consortium College Preparatory High School.

“I would be in the passenger seat and think, this is crazy. Who owns this building? Who will take ownership of this building, and why isn’t it fixed? I always had all these questions about it,” she said.

In 2023, five years after Ford Motor Company purchased the train station, Michigan Central posted a job opening for associate director of community engagement. With just eleven months until the grand opening, there was still plenty to be done.

Alvizo was working as the program director for Detroit Means Business at the Detroit Economic Growth Corporation and was interested in the job.

“It seemed like all the things I love to do: being in communities, talking to people, and thinking through creative problem-solving and innovation work,” Alvizo said.

Michigan Central’s executives wanted a strategic thinker—someone who could help advance their vision of fostering community relationships and transforming Michigan Central into a hub for mobility, technology, and entrepreneurship while attracting startups.

Seventy-five people applied for the job, but Alvizo, a 27-year-old Latina, stood out for her ability to speak about innovation as a way to dismantle barriers.

“Hiring Alondra was the best decision we made,” said Cornetta Lane-Smith, director of community engagement at Michigan Central. “She had a grasp of how to move something from not existing to existing, and we needed someone who could think tactically about projects in that way.”

Days after starting her new job, Alvizo stepped into Michigan Central for the first time. She was struck by the grandeur of the 120-year-old beaux-arts building. Michigan Central’s dramatic interior was still under construction. Its grand hall, which spans 19,500 square feet, was encased in scaffolding, and thousands of skilled workers—many specializing in historic preservation—labored tirelessly to complete the highly anticipated landmark.

“I remember walking through the east entrance in just deep awe, knowing how many people had to come together to make this happen,” Alvizo said. “What an honor and privilege of a lifetime to be able to give this building back to Detroiters.”

Alvizo started at Michigan Central by building systems around project management to streamline the work ahead.

Lane-Smith said, “Michigan Central is a startup, so there are a lot of things that we are still building. So when Alondra came in, she was like, okay, where are all the documents? Where is the structure? Where are the things? And we didn’t have any of that. Alondra came along and built some of that infrastructure to help us be organized and for us to keep track of all the things that we have to do,” she said.

Beyond building infrastructure, one of Alvizo’s first initiatives as the new associate director of community engagement was to work on the newsletter, which opened a direct line to the surrounding community so she could inform people of what was happening at Michigan Central.

The bilingual publication is distributed in both print and email. As a Spanish speaker, Alvizo noticed that the marketing firm’s translations used formal, corporate Spanish that didn’t truly capture the community’s voice.

“We switched our vendors to make sure that more money was going to local community folks to do this translation work,” Alvizo said. “People don’t often think about budgeting for translation, but it’s an important component.”

Alvizo, who holds a master’s degree in urban planning, is passionate about the role small businesses play in creating walkable neighborhoods, particularly in Southwest Detroit, where she grew up.

So when the Mexicantown Main Street program, an initiative of the Southwest Detroit Business Association (SDBA) aimed at helping small businesses enhance and beautify their facades, faced an uncertain future, Alvizo advocated for funding to support the program.

“I was the primary champion of investing in the Mexicantown Main Street program at SDBA through the community benefits agreement commitments. I had been in this role for about four months when I advocated for this investment,” Alvizo said.

SDBA didn’t have direct funding for the Main Street program. “The $150,000 grant from Michigan Central allowed us to hire José Maldonado to be a full-time director,” said Greg Mangan, real estate advocate at SDBA.

Mangan says the money “helps improve the facades of older legacy buildings, commercial facades that are more inviting for the community. Somewhere where kids walk by and don’t have bars on the windows, where there are nicer awnings instead of defensive architecture, where it looks like they are trying to keep people out instead of inviting people in.”

Mangan says that four businesses have been awarded facade improvement grants so far.

June will mark one year since Michigan Central opened to the public. As for Alvizo, she is excited to continue to work closely with the community. She also wants to bring culturally relevant programming to the station, like hosting a Loteria night.

“I call her the daughter of Southwest,” says her boss, Cornetta Lane-Smith. “She has the respect of everybody. Not only is she a charismatic person, and a smart person, but she’s also a person who is well-connected and knows how to tie all the pieces together. She’s a weaver.”

******

Martina Guzmán is an award-winning journalist and the director of the Race & Justice Reporting Initiative at the Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights at Wayne State University Law School.

EL CENTRAL Hispanic News is partially funded by Press Forward, the national movement to strengthen communities by reinvigorating local news. Learn more at www.pressforward.news