Reprinted from Outlier Media and written by Malak Silmi

It’s been almost a year since Detroit announced its ambitious plan to get faster internet into the city by building its own high-speed internet infrastructure in Hope Village, but little to no progress has been made, yet. The project hasn’t been shelved, though — and the city’s new digital equity director has it high on her priority list, among other initiatives to close the digital divide.

Mayor Mike Duggan appointed Christine Burkette to lead the city’s digital inclusion and equity efforts last month after a months-long national search to find a replacement for Joshua Edmonds, Detroit’s first digital inclusion director.

Burkette, a native Detroiter, told Outlier Media that she’s hopeful the city will identify a contractor to install fiber optic lines for the Hope Village project in the next few months and soon be able to break ground. The federally-funded pilot program — spurred by the neighborhood’s 45-day internet outage during the pandemic — will let the city create its own infrastructure for internet service providers (ISPs) to use, ideally increasing service reliability and driving down costs. The project stalled last summer after no vendors bid for the construction work.

The number of Detroit households without internet at home has come down in the last few years but still hovers at nearly 12%, according to 2021 American Community Survey estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau. One in four households didn’t have internet three years prior. Nationally, about 7% of households have no internet access.

Burkette said she’s been working up to 12 hours most days since she started the job. Her desk is littered with sticky notes filled with the different tasks, projects and issues she’s beginning to tackle to close the digital divide.

“It takes a lot of work to support over 600,000 residents, so trust me when I say there’s barely enough time to eat right now,” she told Outlier.

Burkette is part of a small team of three working in the Digital Inclusion and Equity office. She is the CEO and founder of Promising Integrations Consulting Firm Inc. and worked as the chief information officer for the Detroit Public Schools Community District from 2017 to 2018. Burkette is taking a six-month sabbatical from her firm to focus on her new role.

One of her early projects is building a data dashboard to identify internet needs by neighborhood and by district, and it is set to launch in two weeks. The dashboard will include demographics of some people who may have greater internet connectivity needs like the elderly, veterans and people with disabilities.

Duggan said in a press release that having Burkette as a leader will help Detroit continue on its “path to become one of the most connected cities in America.”

Chipping away at the digital divide, from subsidies to hotspots

A national investigation by The Markup last fall revealed that internet companies provide slower service to poorer cities, including Detroit, for the same price as customers in other cities get for faster internet. Burkette said her office is hoping to engage in some conversations with ISPs in the next few months to increase access to high-speed internet.

“In the meantime, we’re also offering a lot of subsidies so that (residents) can afford the high-speed internet if they have any type of issues with income,” she said.

While more Detroiters have gotten some access to the internet in recent years, there are still significant gaps — Burkette said the city’s most recent data, captured from several national sources, shows about 43% of Detroit households lack access to high-speed internet, and 32% of households only have one smartphone or no device at all.

Detroiters can access current assistance including monthly internet service discounts for lower-income households through a federally-funded program that has enrolled more than half of eligible households in the city in less than two years — one of the highest enrollment rates nationwide. Residents can also use technology centers across the city that help with technology and offer free Wi-Fi through the Connect 313 initiative.

Burkette is considering additional connectivity programs like more subsidized services, promoting small businesses that offer free internet and distributing hot spots and Wi-Fi extenders directly to Detroiters to “see how that helps each of our individual homeowners in getting that Wi-Fi connectivity that they need.”

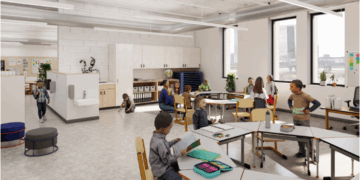

Burkette has experience identifying individual connectivity challenges — like when it turned out that some Detroit teachers, during her time at the school district, were having internet issues when they closed their classroom doors because the thick cinder-block walls already weakened Wi-Fi signals. Hot spots were then installed in the affected schools, and teachers have since reported more stable connectivity, Burkette said.

Burkette faces a significant challenge ahead if she’s to succeed at making Detroit “one of the most connected cities.” As she sees it, pressing ISPs for better service is only one piece of a strategy that attacks the problem from many angles.

“One solution that works for one area is not going to work for every area. It’s different issues,” Burkette said. “A lot of times, the bandwidth issue is not really the provider. It may be the whole structure.”