“It’s for la Migra,” was the phrase Evan, a member of Asamblea Popular Detroit, used to break the ice. Evan had approached a group of workers who were buying Mexican food for breakfast at a gas station on Livernois Avenue in Southwest Detroit. The dozen laborers did not speak English. Evan, with halting Spanish, tried to offer and explain what he had in his hand: a whistle. One by one, the workers—though hesitant—began to take the packages of whistles that Evan, along with other volunteers, had assembled by the hundreds earlier that day. Adopted since November, it was a routine distribution of whistles with instructions at local businesses, restaurants, and gas stations in the area.

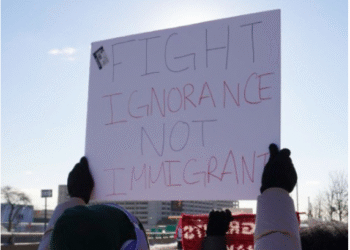

January 20 marked one year since Trump returned to the White House. Nationwide, the portraits of empty cars with shattered windows, people being thrown to the ground and arrested by multiple ICE agents, citizens and migrants being threatened and shot, summarize the first year of the immigrant crackdown that Trump has launched.

After the death of Renee Good at the hands of an immigration agent came the Trump Administration‘s endorsement of an “absolute immunity” for immigration officers. K–12 students arrested and sent to detention centers or deported. And while videos of immigration agents asking for documents based on skin color or accents in Minnesota go viral, communities and activists are seeking new ways to protect one another.

In Michigan, across the Lower Peninsula, from transportation networks, whistles, fundraisers, to patrols and monitoring ICE presence, communities from Grand Rapids to Detroit have adopted self-defense methods because of their effectiveness against these agents in cities like Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York.

“Students are going to school with fear; there is a lot of fear even among U.S. citizens,” adds Pauli Astudillo, a member of Asamblea. “And the first step to breaking fear is coming together and helping one another in whatever way we can.”

Verónica Rodríguez carries more than one of these whistles; she keeps them close in case she has to use them or give them to someone else. It’s almost 6 a.m. on January 13th, and messages from neighbors about ICE presence are arriving on her phone. In a WhatsApp group, she coordinates with two other drivers who can confirm that location. This time it will be Vero, as they affectionately call her; she, along with other drivers, patrols the streets of Southwest Detroit, alerting people to determine the presence of ICE agents through broadcasts and Facebook posts.

Since April, Vero has defined schedules and routes. Trucks and SUVs with tinted windows and vehicles left in unusual or no parking areas are potential suspects. Upon arriving at the sighting area, Vero finds an abandoned white truck; the people who were inside have already been arrested. She takes photos and updates that the area is now clear. The other drivers arrive,

try to find information about the vehicle to notify family members, and coordinate for a tow truck to remove it.

In cities like Grand Rapids, Pontiac, and Detroit, ordinary citizens have been patrolling and alerting the community so they can maintain their daily routines. For Rodríguez, it has become a responsibility because she does not want to see her neighbors in detention centers or deported. “People wait for our messages so they can go out to buy food, medicine, and all that,” Rodríguez says. “They are people at risk who need care, and they always thank us. They have also learned to report, but they also depend on our alerts. That’s how the community becomes empowered.”

Although there have not been immigration raids like those in Los Angeles, Chicago, or Minneapolis in Michigan, for many activists, it is not far-fetched to think that Detroit or Grand Rapids could be next. Here, daily ICE arrests have increased by 230% compared to 2024, according to MLive, and deportations have increased by 123% over 2024. Jeff Smith of GR Rapid Response to ICE says that the presence of immigration agents has intensified since June and that they maintain surveillance and arrest tactics during morning activities.

Together with the Cosecha movement, GR Rapid Response works to “minimize the harm that is directed at immigrants.” Transportation networks to court appointments or daily shopping, protests in favor of sanctuary policies, fundraising for family support, and legal expenses are some of the ways they help. Both groups began in 2017.

“Most of the people who are detained are the main economic support of their families. From one moment to the next, households are left without income, and they still have to pay rent and buy food,” Smith points out.

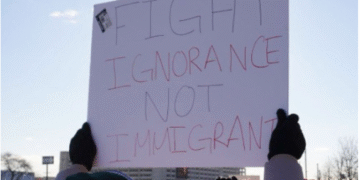

Last year, during Trump’s inauguration as the 47th president of the United States, temperatures in Michigan were in the single digits. In downtown Grand Rapids, activists from the Cosecha movement marched against the anti-immigrant crusade that was to come. “Deportations are problems that immigrants have always had to deal with, whether under this government or the previous one. We want to put an end to that. They are just the same coin with a different face,” said Gema Lowe, a member of Movimiento Cosecha, on that occasion.

Since then, complaints about collaboration between local police and ICE and demands over sanctuary policies in Grand Rapids and Kent County have become constant pressure amid refusals by Mayor David LaGrand, who considers them “false hope.” On the afternoon of January 6, five volunteers from Cosecha and GR Rapid Response were arrested inside the Kent County Sheriff’s building. They were protesting alleged collaboration between the county sheriff’s office and ICE, in which immigrants were being held longer until ICE arrived, despite being ready for release.

In Detroit, on Tuesday, January 13, the term “sanctuary” was on the lips of politicians, activists, and community members. During the Detroit City Council meeting, residents demanded strong actions and sanctuary policies to protect immigrants. Two miles away, at the Motor City Casino Hotel, Trump, in his speech, threatened that every sanctuary jurisdiction will lose all federal funding starting February 1.

Fernando Ramírez, 66, went through two processing centers before being sent to the North Lake Processing Center in Baldwin. Ramírez, who has a legal work permit, was arrested by ICE subcontractor agents in October 2025 while weighing the trailer he was driving.

For his daughters, Samantha Ramírez, 37, and her sister Nahomi, 30, it was a blessing that he was taken close to them. They live 40 minutes driving from Baldwin and began offering help to other detainees that her father befriended inside. They created Raices Migrantes to provide support to those held inside North Lake, including financial assistance, communication with the outside, and transportation to reunite them with their families.

“What we’re doing is making sure detainees have someone; that they know there are people out here fighting for them,” Samantha says. “We put a little bit of money into each account. Even though it wasn’t much, for them it was everything, because that’s how they talk to their families and buy some food to be more comfortable.”

Since North Lake opened in the summer of 2025, its detainee population grew from 28 in August to 1,352 by the end of November, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). Representative Rashida Tlaib (MI-12) described the facility as having “dehumanizing conditions” after a visit in early December.

Reports of mistreatment, poor food, suicide attempts, and the most recent death of a Bulgarian immigrant in mid-December—whom ICE said died of natural causes—set off alarms among everyone arrested by federal agents and their families.

When a detainee is released, families are notified with very little notice. From there, a transportation network, in coordination with other drivers, helps released detainees reunite with their families in states such as Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin.

On the evening of December 12, Fernando Ramírez was released following an Habeas Corpus. The family reunions that the Ramírez sisters made possible for dozens of released detainees they were finally experiencing themselves. On the way home, tears, kisses, and hugs did not stop during a nearly an hour-long drive. Now, Raíces Migrantes will maintain greater contact with detainees to give them a voice outside.

“What all of us do is a reminder that there are more good people than bad—it’s just that right now the bad ones are a little stronger,” Samantha concluded. “But we must keep fighting for our right to live in peace.”

Luchando por el derecho de vivir en paz

La represión de inmigrantes orquestada por Trump ha llegado a su primer año. En Michigan, miembros de la comunidad organizan métodos de autodefensa para evitar detenciones y deportaciones.

“Es para la migra”, fue la frase que Evan, miembro de Asamblea Popular Detroit usó para entrar en confianza. Evan se había acercado a un grupo de obreros que compraban comida mexicana para desayunar en una estación de servicio en la avenida Livernois, en Southwest Detroit. La docena de obreros no hablaba inglés. Evan, con un español masticado, intentaba ofrecerles y explicarles lo que tenía en la mano: un silbato. Uno a uno, los obreros, aunque vacilantes, comenzaron a tomar los paquetes de silbatos que horas antes Evan, junto a otros voluntarios, armaron por centenares. Adoptado desde noviembre, lo de hoy fue una distribución rutinaria de silbatos con instrucciones en bodegas, restaurantes y gasolineras de la zona.

EL 20 de enero se cumplió un año desde que Trump volvió a la Casa Blanca. A nivel nacional, la imagen de autos vacíos con las lunas destrozadas, Personas siendo tiradas al suelo y arrestadas por múltiples agentes de ICE, ciudadanos y migrantes amenazados y baleados resumen también el primer año de la cacería inmigrante que el republicano ha iniciado.

A la muerte de Renee Good por un agente migratorio, le siguió la “inmunidad absoluta” avalada por la administración de Trump para oficiales federales. Estudiantes K-12 arrestados y enviados a centros de detención o deportados, y mientras videos de agentes migratorios pidiendo documentos a personas de piel oscura con acento fuerte en Minnesota se vuelven virales, comunidades y activistas buscan nuevas formas de protegerse entre ellos.

En Michigan, a lo largo de la baja península, desde redes de transporte, silbatos, colectas de dinero y hasta patrullajes y monitoreo para advertir la presencia de ICE, comunidades desde Grand Rapids hasta Detroit se han contagiado de métodos de autodefensa debido a su efectividad contra agentes migratorios en ciudades como Chicago, Los Ángeles y Nueva York.

“Los estudiantes están yendo a la escuela con miedo; hay mucho miedo incluso entre ciudadanos estadounidenses”, agrega Astudillo, miembro de Asamblea. “Y el primer paso de quebrar el miedo es juntarnos y ayudarnos unos a otros en lo que podamos.”

Mientras maneja, Verónica Rodríguez carga más de uno de estos silbatos; los tiene cerca en caso de que tenga que usarlos o dárselos a alguien más. Son casi las 6 am y al celular le llegan mensajes de vecinos sobre avistamientos de ICE. En un grupo de WhatsApp coordina con otros dos conductores quién puede confirmar la ubicación. Esta vez irá Vero, como la llaman de cariño; ella, junto con otros conductores, patrulla las calles de Southwest Detroit avisando de la presencia de agentes federales a través de transmisiones y publicaciones en Facebook.

Desde abril, Vero ya tiene horarios y rutas definidas. Camionetas y SUVS con lunas polarizadas, mal estacionados en lugares no adecuados, son potenciales sospechosos. Al llegar a la zona del avistamiento, Vero encuentra una camioneta blanca abandonada; las personas que iban adentro ya fueron arrestadas. Ella toma fotos y actualiza que la zona ya está limpia. Sus compañeros llegan, intentan averiguar los datos del auto para avisar a los familiares y coordinan para que una grúa remolque el auto.

En ciudades como Grand Rapids, Pontiac y Detroit, ciudadanos comunes han venido patrullando avisando a la comunidad para que mantenga su rutina diaria. Para Rodríguez, ya es una responsabilidad, pues no quiere ver a sus vecinos en centros de detención y luego deportados. “La gente espera nuestros mensajes para salir a comprar comida, medicinas y todo eso”, cuenta Rodríguez. “Son personas en riesgo que necesitan cuidado y siempre nos agradecen. Ellos también han aprendido a informar, pero también dependen de nuestros avisos. Es así como se va empoderando a la comunidad.”

Aunque en Michigan no ha habido redadas migratorias como en Los Ángeles, Chicago o Minneapolis, para muchos activistas no es descabellado pensar que Detroit o Grand Rapids sean las siguientes. Aquí, los arrestos diarios de ICE se han incrementado en 230% en comparación con el 2024 según MLive, y las deportaciones se incrementaron en 123% más que el 2024. Jeff Smith, de GR Rapid Response to ICE, afirma que la presencia de los agentes migratorios se ha intensificado desde junio y que mantienen tácticas de seguimiento y arresto durante actividades matutinas.

Junto al movimiento Cosecha, GR Rapid Response trabaja para “minimizar el daño que está dirigido a inmigrantes”. Redes de transporte hacia citas de corte o compras diarias, protestas a favor de políticas de santuario, recaudación de fondos para sustento familiar y gastos legales son las formas en que ayudan. Ambos iniciaron en 2017.

“La mayoría de las personas que son detenidas son el principal sustento económico de sus familias. De un momento a otro los hogares se quedan sin ingresos y aun así tienen que pagar la renta y comprar comida”, señala Smith.

El año pasado, durante la investidura de Trump como 47.º presidente de EE.UU., en Michigan, la temperatura marcaba un dígito. En el centro de GR, activistas del movimiento Cosecha marchaban en contra de la cruzada antiinmigrante que se avecinaba. “Las deportaciones son problemas que los inmigrantes hemos tenido que lidiar siempre, ya sea este gobierno o el anterior. Queremos terminar con eso.

Ellos son solo la misma moneda con distinta cara.” Dijo Gema Lowe, miembro de Movimiento Cosecha, aquella oportunidad.

Desde entonces, las denuncias por la colaboración de la policía local con ICE y las demandas por políticas santuario en GR y en el condado de Kent se volvieron una presión constante ante las negativas del alcalde David LaGrand, quien las considera “falsa esperanza”. La tarde del 6 de enero, cinco voluntarios de Cosecha y GR Rapid Response fueron arrestados dentro del edificio del sheriff de Kent. Ellos protestaban contra una supuesta colaboración entre la oficina del Sheriff del condado y ICE, en donde se retenía a inmigrantes por más tiempo hasta la llegada de ICE, a pesar de haber estado listos para ser liberados.

En Detroit, el martes 13 de enero, el término santuario estuvo de boca en boca entre políticos, activistas y miembros de la comunidad. Durante la reunión del Consejo Municipal de Detroit, residentes demandaban acciones sólidas y políticas de santuario que protejan a los inmigrantes. A dos millas, en el Motorcity Casino Hotel, Trump, en su discurso, amenazaba con que toda jurisdicción santuario perderá todo financiamiento federal a partir del 1 de febrero.

Fernando Ramírez, de 66 años, pasó por 2 centros de procesamiento antes de ser enviado a North Lake, en Baldwin. Ramírez, quien cuenta con permiso de trabajo legal, fue arrestado por agentes subsidiarios de ICE en octubre de 2025, mientras pesaba el tráiler que conducía.

Para sus hijas, Samantha Ramírez, de 37 años, y su hermana Nahomi, de 30, fue una bendición que lo llevaran a un lugar cercano a ellas. Viven a 40 minutos en auto de Baldwin y comenzaron a ofrecer ayuda a otros detenidos a medida que su padre hacía amistades dentro. Crearon Raíces Migrantes para brindar apoyo, que incluye ayuda financiera, comunicación con el exterior y transporte para reunirlos con sus familias.

“Nació de chiripa. Lo que estamos haciendo es asegurar que los internos tengan a alguien; que sepan que hay personas acá afuera que están peleando por ellos”, cuenta Samantha. “Les depositamos un poquito de dinero a cada uno. Aunque no es mucho, para ellos era todo, porque así hablan con su familia y compran algo de comida para estar más cómodos.”

Desde que North Lake abrió en el verano del 2025, pasó de 28 internos en agosto a 1352 para finales de noviembre, según el Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). La legisladora Rashida Tlaib (MI-12) la calificó de “condiciones deshumanizantes” después de una visita a inicios de diciembre.

Las denuncias de pésimos tratos, mala alimentación, intentos de suicidio y la última muerte de un inmigrante búlgaro a mediados de diciembre, al que ICE calificó de causa natural, zanjaron las alertas en todo aquel arrestado por agentes federales y sus familiares.

Cuando un interno es liberado, la familia de este es avisada con muy poca anticipación. Desde allí una red de transporte, en coordinación con otros conductores, ayuda a los internos liberados a reencontrarse con sus familias en estados como Illinois, Indiana y Wisconsin.

La noche del lunes 12 de diciembre, el Sr. Ramírez fue liberado. Las reuniones entre familias que las hermanas Ramírez lograron a decenas de internos liberados, ahora son vividas por ellas. De regreso a casa, las lágrimas, los besos y los abrazos no cesaban en casi una hora de vuelta a casa. Ahora, Raíces Migrantes mantendrá mayor contacto con los internos para darles voz en el exterior.

“Lo que todos hacemos es un recordatorio de que hay más gente buena que mala, nomás que ahorita los malos están un poquito más fuertes”, zanjó Samantha. “Pero nosotros debemos seguir peleando por nuestro derecho de vivir en paz.”