While tamales can be found throughout Southwest Detroit year-round, the holidays are synonymous with tamale season. More than any other time of year, the month of December is when families make, eat, buy and share tamales.

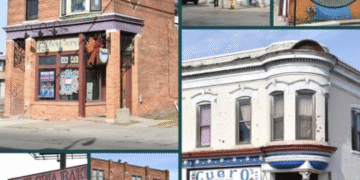

Coahuila, Mexico - Prince Valley

To keep up with demand, community grocers, restaurants and tamalerias ramp up production of ready- to-eat tamales. According to Prince Valley Market kitchen manager, Brenda Ramirez, her team of women makes more than a thousand tamales each weekday morning.

Mexican tamales are hugely popular in Southwest Detroit. Because of the diverse makeup of the community, tamales can differ in ingredi- ents, style and technique from location to location. Ramirez is from Coahuila in the north of Mexico. The style of masa she uses at Prince Valley Market is moist and spongy with a distinct flavor profile.

Oaxaca, Mexico – Caterer Jessica Gómez

Mexican tamales can vary greatly depending on the region. Caterer Jessica Gómez is from Oaxaca, Mexico, where indigenous dishes are typical. She makes tamales cooked in banana leaves.

The tamal in Latin American culture is as iconic as it is ancient. It predates Spanish Colonialism by thousands of years, tracing its origin back to Mesoamerica.

Because they’re so tradi- tional, many people might only be familiar with the recipes they grew up eating with their families. But tamales are as diverse as they are loved. In Mexico alone, there are at least

350 types, according to the “Diccionario Enciclopedico De Gastronomia Mexicana,”

an authoritative resource on Mexican cooking and cuisine. Many of the ingredients that

Gómez uses in her cooking are imported from a specific area in Chiapas.

Commonly, Mexican tamales are made with a meat filling and lard in the masa – but not all. Chipilin tamales are vegan. The leafy green is used in many south- ern Mexican and Central American dishes.

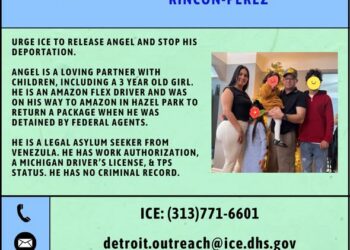

Puertorican – Dominican –Rincon Tropical

Mexican tamales aren’t the only varieties Southwest has to offer. Rincon Tropical, located on Michigan Avenue just west of Livernois, is owned by Lisaida Moreno, who is of Puertorican descent, and her husband, Riquelmi Moreno, who is Dominican. Their restaurant serves a fusion

of both cultures, including

a type of tamal known as pasteles en hoja.

A holiday essential, paste- les en hoja are wrapped in banana leaves. The dough is made from green plantain.

It has a savory taste and a moist, melt-in-your-mouth texture. Pasteles en hoja are usually stuffed with olives and either pork or chicken . To hold their shape they’re wrapped in wax paper and tied with string. According

to Moreno, there is a debate over whether pasteles are best eaten with ketchup or hot sauce.

Venezuela-Caracas – El rey de las arepas

In Venezuela, tamales are called hallacas. The ingre- dients vary from region to region. Popular Southwest Detroit Venezuelan restau- rant, El Rey de Las Arepas, makes a version from the capital region of Caracas.

The corn dough, pre-cooked corn flour—which is similar to the masa used in arepas— is brushed with achiote, which gives it a distinctive

color and slightly sweet, nutty flavor.

At El Rey de Las Arepas, hallacas are made with a combination of chicken, beef, pork, peppers, olives, raisins and chickpeas layered onto a thin layer of the masa.

The hallacas are then wrapped in banana leaf and tied. Because hallacas are

so time-intensive, El Rey de Las Arepas only makes them

for preorders, and they’re only available through the holidays. During that time, Gutierrez and co-owner Jacqueline Alejandre are joined by Gutierriz’s mother, Zoraida Gutierrez, to help make the hallacas and guide the process.

Ofelia Saenz is a native of Southwest Detroit and a writer, marketer and food entrepreneur. She writes about entertainment, arts, culture and other human-interest stories for EL CENTRAL.

Alejandro Ugalde (Kopalli Media) is a Mexico City immigrant and visual storyteller with a deep love for Detroit and its multiculturalism.