By Ozzie Rivera

Reprinted from EL CENTRAL Hispanic News, January 30, 2020

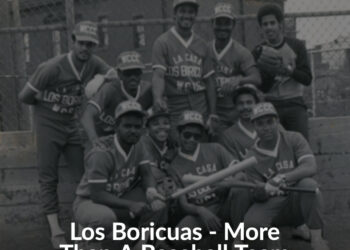

Soon after Puerto Ricans (Boricuas-Puerto Rico’s original indigenous term) were made U.S. citizens through the Jones Act of 1917, which coincided with the U.S.’ entry into World War I, Puerto Ricans were recruited to work in significant numbers in the shipyards of New Orleans. Within a year, close to 100 Afro-Boricuas single males had settled on the near east side near Woodward, on the western edge of what would become known as the African American community of Black Bottom.

In 1971, I was a freshman at Wayne State University in the newly established Latino En Marcha program, a collaborative effort between the University (WSU), LA SED and New Detroit. The program would later be renamed Chicano-Boricua Studies and is now known as WSU’s Center for Latino and Latin American Studies. During our second semester, students were assigned the task of conducting community projects. Three of the close to forty students, Miqueas Bermudez, Rosa Del Valle and I were Puerto Rican and we decided to conduct a research project on the Puerto Rican population in Detroit.

What I did not realize at that moment was that much of the information gained through our humble efforts would fill in a missing part of our history in Detroit. In some real ways, this project changed my life as it unleashed in me a strong appreciation for and interest in the power of oral history.

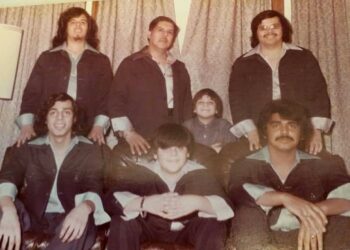

My father, “Tite” Rivera-Malave, upon hearing of our project told me there were some elders from our hometown area on the island, Juana Diaz and Ponce, who had arrived in Detroit early on in the 1900’s and had settled in the historic Black Bottom area. One cold snowy day in January 1972 he, along with my uncle Ismael Rivera and a friend Manuel Rivera who was also from our home town Juana Diaz, took me over to the near east side to meet a number of elders.

My conversation with Juan Santos who at that time was 75 years old, Carlos Rivera and Eugene Rivera aged 74 yrs. was significant in reframing my understanding of the Puerto Rican presence here in Detroit. Born just before Puerto Rico was taken by the U.S. they witnessed the transition from being a Spanish colony to American control. In 1917 when the U.S. entered World War I they were part of a group of hundreds if not thousands of Puerto Ricans who either went to war and saw action in Europe, many as part of the famed black American battalion the Harlem Hellfighters and the all Puerto Rican 365 Infantry, affectionately known as the Borinqueeners. Many others were sent to build ships in New Orleans. After the war’s end, many returned to the island but a significant number remained on the mainland.

In the interview the three recounted how they and many others in this wave of Boricuas ended up in Detroit after first traveling through Louisiana, slowly moving up through other southern states before arriving here. Without exception, they reflected their

disgust and shock at the Jim Crow laws and practices they encountered in the south. Some of them first went to New York, which was becoming a growing destination for the islanders. But a number of them felt alienated in the big city environment and eventually decided on Detroit because of its booming job market. Juan Santos arrived in 1918, and found about 100 Puerto Ricans already settled here. Eugene and Carlos arrived within a couple of years after that. Another wave of migrants joined them during the period of 1927-28 fleeing the aftermath of a major hurricane that rocked Puerto Rico. This older Boricua community set up a social club that met into the early 1960’s.

Though some of this original community returned to the island for a period of time, a number returned back to Detroit by the 40’s permanently settling in Black Bottom and marrying into the African American community.

A separate group of islanders settled in the Most Holy Trinity and Ste Anne’s barrios in the late 40’s and 50’s attracted to those areas because of the large Spanish Speaking Mexican American community. Meanwhile the older established community was slowly being decimated through the passing of some, the acculturation into the African American community and very significantly by the construction of I-375 and subsequent destruction of Black Bottom.

As a young community activist, I remember running into “Riveras”, “Rodriguezes” “Gonzalezes” etc. in other parts of the city, who had grown up culturally African American but upon further discussion shared that their fathers or grandfathers were part of this first Boricua community.

Almost two decades later, during the 90’s, I was contacted by Darcy Coles, a Puerto Rican/African American historian who at that time was based in California and writing a manuscript on Puerto Ricans outside of the New York/east coast corridor. He happened to run across an article the Archdiocese of Detroit’s Hispanic Ministry had written on my research. We shared information for almost a decade and soon found out to my surprise the New Orleans connection would become a goldmine. Darcy found out that other Boricuas in the hundreds had fanned out from New Orleans throughout other parts of the country right after end of World War I in a chapter of our history that had not been told.