Reprinted from Today@Wayne

Undergraduate admissions counselor Vanessa Reynolds ‘03, ‘07, ‘23 and her family moved to the United States when she was 11. She said the transition was difficult.

“I didn’t know English,” she said. “I attended St. Stephen’s, a Catholic school in southwest Detroit that didn’t have bilingual education. There was a staff member — I don’t even think she was a teacher — there who was Mexican American. They asked her if she would help me, so she would pull me from class a few hours every day, and that is how I learned English. I will forever be grateful to Anita.”

Learning to speak English was not the only adjustment Reynolds and her family had to make.

“We lived in a very small town in Mexico, and Detroit was a big city,” she said. “Mexico was warm, and we moved in January, right in the middle of winter. In Mexico, we attended school in the afternoon, and here, we started at eight in the morning.”

Reynolds knew she wanted to go to college, but she was not sure what university she should choose. During her senior year at Western International High School in Detroit, Juan Jose Martinez — a former counselor from Wayne State’s Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies and now principal at Cesar Chavez Academy — visited the school.

“When I heard about the center, I was impressed,” she said. “I decided I wanted to start out in a small community and then branch out into the university. That was one of the best decisions I have ever made. I don’t think I would be here without the center.”

When Reynolds realized she needed a graduate degree to advance in her career, she earned a master’s in educational leadership from Wayne State in 2007. She decided to pursue a doctorate in educational leadership and policy studies to continue her professional advancement and to increase the number of Latinas achieving doctoral degrees.

“Earning a doctorate was not one of my goals,” she said. “However, while serving on university hiring committees, I noticed that many of the individuals applying for administrative jobs had doctoral degrees. If I decide to make that transition, I want to be ready.”

An active member of the university community, Reynolds is a member of the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) Council and the past chair of the Latinx Faculty and Staff Association.

“The association is growing,” she said. “I’m very proud to be a member. We host numerous events and collaborate with other affinity groups across the university to provide support and resources for our Latinx faculty, staff and students and individuals from other historically marginalized groups.”

Reynolds is also involved in the community. She is co-chair of Advocates for Latino Student Advancement in Michigan Education, a nonprofit that promotes the importance of higher education to Latino students throughout the state, awards scholarships to students and hosts an annual conference. As a new member of MANA de Metro Detroit, she is excited to mentor young Latinas.

Reynolds recently received two awards as a testament to her service and commitment: the WSU Academic Staff Professional Development Committee’s Professional Achievement Award and the Hispanic/Latino Commission of Michigan’s Honorary Tribute Award.

Reynolds hopes she has set a good example for her siblings and is proud of their collective accomplishments. They have all attended college, earning four bachelor’s, three master’s, and now, one doctorate. One of her sisters — who is also a Wayne State graduate — is pursuing an education specialist certificate while serving as principal at an elementary school. Reynolds said her parents played a pivotal role in their success.

“Even though my parents didn’t go to college, they made sure that we had access to all the resources we needed,” she said. “I always felt supported.”

Reynolds said her dissertation, “The Testimonios of Latina Higher Education Leaders at Four-Year Predominantly White Institutions in Michigan,” is the first study exploring experiences of Latina non-academic administrators in higher education in the state and one of the hardest things she has ever done. She managed to complete it while working full-time and being a devoted wife and mother.

“My daughter is a cheerleader, one of my sons plays football, and the other one plays baseball and basketball,” she said. “It was difficult getting them back and forth to school, practices and games, but I would take my books and read. My husband and I are a team, so we navigated it all together. My kids were also supportive. It was hard work and a huge commitment, but I wanted to finish, so I persisted.”

Reynolds named her research participants after and dedicated her dissertation to 10 women — including her grandmother, mother and aunt — who were inspirational and instrumental to her growth and development.

“My aunt passed away in January,” she said. “I went to Mexico for the funeral, and I took my research so I could write while I was there. I got a lot done. She was sending me good vibes.”

According to Reynolds, support from faculty was also integral to her success.

“My chair, Dr. Carolyn Shields, was amazing,” she said. “She took me under her wing and made herself available to me. Her feedback was extremely helpful. Dr. William Hill reminded me that I was trying to graduate — not solve the world’s problems. Dr. Sandra Gonzales was wonderful. The fact that she’s also Latina and could relate to what I was writing in my dissertation and that I could reach out to her was extremely helpful. Representation matters.”

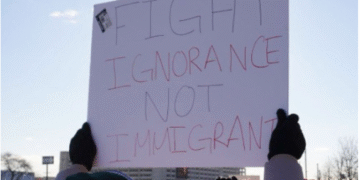

According to Hispanic Outlook on Education, Hispanic and Latino students represent about 17% of doctoral students. Reynolds hopes earning her degree and shedding light on the doctoral experiences of other Latinas will increase this number.

“Knowing few Latinos earn advanced degrees should motivate others to attend graduate school,” she said. “My research participants are examples of what we can accomplish. I want to show the future generation of Latinas — especially my daughter, nieces and goddaughter — that with hard work and perseverance, they can accomplish anything.”