Published in collaboration with Bridge Detroit

On a cold day in January, Carmen (not her real name) carried her ten-month-old baby boy down Vernor Highway in Southwest Detroit. In a moment of panic and desperation, she left the apartment she shared with five other people and went outside for air. Though the temperature was just above freezing, she wore flip-flops and a tank top — she had no winter coat or boots for herself or her baby.

Carmen is 22 years old and one of the hundreds of Venezuelan refugees who have arrived in Detroit — just some of the millions who have fled the country’s totalitarian government and economic crisis. The situation there has become so dire with starvation and crime that 7.3 million Venezuelans have been displaced.

“The desperation in Venezuela is everywhere,” Carmen says.

Her journey began in 2017 and took her to Colombia and Ecuador before she crossed the dangerous Darién Gap on her journey north to the U.S. border, with stops in El Paso, Texas and New York City.

Detroit has not seen the same influx of Latin American migrants as New York, where the mayor has declared it as a humanitarian crisis. Still, social service agencies such as the Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation are rapidly preparing to deal with the health and well-being of the migrants once they arrive.

Angie Reyes, executive director of DHDC, said her team noticed migrants trickling in late last year before a large influx during the holidays when Carmen arrived. Reyes says DHDC has helped about 200 people.

“We’re trying to connect (migrants) to resources, get them clothing, diapers, and essentials.”

Mary Carmen Muñoz, executive director of Latin Americans for Social and Economic Development (LA-SED), said her organization, which also works with recent immigrants and refugees, has seen a significant increase in Venezuelan newcomers. Many of them are families arriving without clothing for winter.

“The environment challenges them,” Muñoz said. “We provide immediate relief and work with Freedom House (temporary home for asylum seekers from around the world) to help find housing.”

No safe place

Carmen’s journey to Detroit had many stops.

After leaving her home, Carmen tried her luck in neighboring Colombia, which is host to the largest community of Venezuelan refugees in the world.

She arrived with only a backpack, part of a crowd of other refugees. She dodged the scam artists and con men who prey on frightened newcomers and walked and hitched rides until she arrived in Barbosa, a small city outside Medellín – Colombia’s second-largest city – and tried to settle in.

Carmen got a job as a cook at a small restaurant, where she says she was treated warmly and respectfully. But the pay was so low she could barely scrape enough money together to afford the low-rate hotel she was staying in despite working seven days a week. After three months, she still had no money for food or anything else. She felt she had no choice but to move on.

An aunt who lived in Ecuador invited her to stay until she got on her feet. Displaced for a second time, she walked miles, took buses and hitched rides to Quito, the capital city of Ecuador, where she would start over again and try to make a go of it.

For five years, it worked. Carmen hustled—cooking and selling arepas on the crowded streets during the day and selling ice cream out of a cooler to passing cars in the evening. She earned enough to rent a room and still have money for groceries. There was life in Ecuador. By 2020, Carmen found a partner who made her happy, and in 2021, she gave birth to a daughter. Perhaps she had finally arrived at her destination, she thought.

But all around her, signs of deepening instability began to show. A growing presence of drug lords and international cartels from Mexico and Albania established routes in Ecuador. They brought with them terrifying violence, leaving Carmen with a constant sense of unease. Every year, she saw things in Ecuador getting worse, not better.

Things have continued to deteriorate in Ecuador. More than a year and a half after Carmen left, armed men stormed into the studio of a major Ecuadorian TV station during a live broadcast as the country watched. The attack came after a series of violent episodes that spread across the country, including explosions and the abduction of police officers.

In August of 2022, Carmen decided to uproot her life again; This time, she set her sights on the United States.

“Any other country was going to be more of the same, more of barely surviving,” Carmen said. “I wanted something better.”

Her despair about finding a better life close to home was not baseless. According to the World Bank, Latin America and the Caribbean have the “undesirable distinction” of being one of the world’s most violent regions.

But for people with little or no money, the journey to the U.S. border is torturous. They cross eight countries and endure weeks, sometimes months, of dangerous travel to reach the border of Mexico and the United States. Migrants face treacherous terrain, exposure to disease and violence at the hands of criminal groups.

Over and over, others warned Carmen of the merciless passage, but she was determined to make this move her last. With her ten-month-old in tow and four months pregnant, Carmen would cross the Darién Gap, a dangerous 66-mile stretch of jungle that connects Colombia and Panama and marks the beginning of the treacherous journey north that would take two months.

“The jungle is a business,” Carmen said. “People shake you down for money as soon as you get there. There is no end to it. At every stretch, someone is there to extort you.”

A treacherous journey

Carmen lived in constant fear of being raped, kidnapped, or killed, but she kept walking through a dense rainforest that draped over steep mountains and vast swamps. She walked past mounds of luggage, clothing, and backpacks left behind by migrants who realized they could no longer carry their belongings. Past armed men and past dead bodies.

“I grabbed a sheet that was on the ground to wrap my daughter in because she had a fever,” Carmen said. “But when I pulled the sheet, there was a dead little boy about three or four years old underneath. Seeing him filled me with horror and panic.”

At last, she reached Panama, but she had to keep walking, crossing through rivers and streams. At one crossing, Carmen lost her grip and was swept away by the river’s strong current.

She had been carrying her infant in her arms, but as the water pulled her away from her group of about 50, she felt someone grab hold of the baby. She let go of her child and was carried away by the river.

“I preferred to let my daughter go to save her. If I didn’t let her go, I would have taken her with me, and she would have drowned,” Carmen said.

The river pulled her in and threw her against the rocks. She started swallowing water and could feel herself drowning. Then, strong hands grasped her. She says a man who knew how to swim came back to save her.

Her daughter, now two, is terrified of water. “Sometimes she screams when I bathe her,” Carmen said. “Tell me, what child screams when getting a bath?”

The rest of her journey was just as dramatic. She walked and hitched rides through the rest of Panama, then Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, and Guatemala, carrying her daughter the whole way. Every day, there was a new struggle, but every day she kept walking.

Mexico, a country rife with cartels, corrupt police, and human traffickers eager to profit from the flow of people headed north, lay ahead of her. As she moved on, Carmen was terrified of being killed, kidnapped, or extorted, which are not uncommon fates for people like her in Mexico, where migration protection rackets are a billion-dollar industry.

Elizabeth Orozco Vasquez, CEO of Freedom House Detroit said “these are not unique stories.”

“We have heard everything. They cross the jungle where there are dead bodies. Men usually make the journey faster, but women and children take longer because they have to hide at night for fear of being raped. All the way through to the northern border, people are being exploited,” Orozco Vasquez said. “We had a woman who came through with two children. She was raped in Mexico. She was seven months pregnant by the time she got to Freedom House.”

Orozco Vasquez adds that “no one takes that kind of journey if their homeland was safe. These people really cannot go back, their countries have collapsed, It’s too dangerous.”

Two months after leaving Ecuador, malnourished, dehydrated, and now six months pregnant, Carmen arrived in Ciudad Juarez. Across the Rio Grande was El Paso, Texas. She crossed that last river and allowed herself to be picked up by Border Patrol agents.

When the police took her into custody, she wept for joy. “I was overcome with a sense of peace when I got to the United States,” said Carmen. “I felt safe.”

Hardships continue

In October 2022, Carmen spent nine days in an immigration detention and processing center, which she describes as a “prison.” Then, a Catholic organization bought her a bus ticket to New York City, where she joined more than 150,000 other new arrivals, a flood of migrants that has strained city services.

Carmen was placed in a Manhattan hotel repurposed for emergency migrant housing and, a few months after arriving, gave birth to a son in a New York City hospital. She felt hopeful about this new life.

But her hopefulness did not last. Soon after her baby was born, her mental health began to deteriorate. “They told me I had postpartum depression,” Carmen said.

For months, Carmen isolated herself in her hotel room. She couldn’t work and struggled to make friends. Sometimes, she would wander down to the lobby of the repurposed hotel, a de facto town square, where migrants and refugees gathered daily. Carmen went there a few times to try and meet people, but fights broke out, which scared her.

“I cried all the time,” she said. “If anyone said anything to me, I would burst into tears.”

As the weeks stretched on, Carmen began cutting herself. She was consumed by depression. After almost a year in that hotel room, she couldn’t take it anymore. In late October of 2023, she took her children back to the NYC Port Authority and boarded a bus, once again leaving an adopted home behind. This time, she was bound for Detroit, where her brother had moved, and he had invited her to join him.

The city of Detroit said it does not have data on the total number of migrants that have arrived here. However, David M. Bowser, chief of housing solutions and supportive services for the city, says there are 144 new arrivals currently occupying beds in emergency facilities.

“The city continues to work closely with our local partners to be aware of and to address the needs of all residents, long-term or new arrivals, of the City of Detroit,” Bowser said.

When she arrived, Carmen found more challenges but also a new home. She recently got a small one-bedroom apartment where she lives with her partner, her two children and her sister.

“I suffered every single day of the journey, I slept in the streets, I was treated so badly, I was so hungry and my daughter’s health suffered. I would never do it again if I knew what it was like,” Carmen said.

Since her panic attack on Vernor Hwy in Southwest Detroit, Carmen has started school, learning how to read, and is settling into her new home.

“For the first time in my life, I feel like I’m one step ahead,” she said.

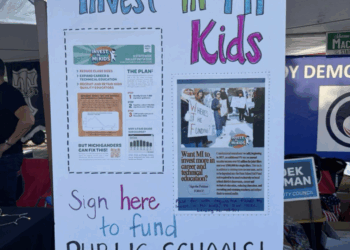

Resources for Migrants in Detroit

Social services

LA-SED: Latin Americans for Social and Economic Development

4138 Vernor Hwy, Detroit, MI 48209

313-554-2025

Mutual Aid

Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation

1211 Trumbull, Detroit 48126

313-967-4880

Church of the Messiah

231 E Grand Blvd, Detroit, MI 48207

313-567-1158

Legal Services

Southwest Detroit Immigrant and Refugee Center

17375 Harper Ave, Suite 24124

Detroit, MI 48224

313-288-9904

Housing

Freedom House Detroit

1777 N Rademacher St, Detroit, MI 48209

313-964-4320

City of Detroit’s Housing & Revitalization Department

Coleman A. Young Municipal Center, 2 Woodward Ave. – Suite 908

Detroit, MI 48226 (313) 224-6380

“Solo quería algo mejor:”la desgarradora travesía a Detroit de una inmigrante venezolana

El suroeste de Detroit enfrenta la afluencia de inmigrantes venezolanos.

En un frío día de enero, Carmen (no es su verdadero nombre) llevaba a su bebé de diez meses por Vernor Highway, en el suroeste de Detroit. En un momento de pánico y desesperación, salió del apartamento que compartía con otras cinco personas a tomar aire. Aunque la temperatura estaba justo por encima del punto de congelación, llevaba chanclas y una camiseta sin mangas; no tenía abrigo de invierno ni botas para ella o su bebé.

Carmen tiene 22 años y es solo una, de los cientos de refugiados venezolanos que han llegado a Detroit, que son solo algunos de los millones que han huido del gobierno totalitario y la crisis económica. La situación se ha vuelto tan grave debido al hambre y la criminalidad que 7,3 millones de venezolanos han sido desplazados.

“La desesperación en Venezuela está en todas partes”, comentó Carmen.

Su viaje comenzó en 2017 pasando por Colombia y Ecuador, antes de cruzar el peligroso Tapón del Darién; en su trayecto hacia Estados Unidos, con paradas en El Paso, Texas y la ciudad de Nueva York.

Detroit no ha visto la misma afluencia de inmigrantes latinoamericanos que Nueva York, donde el alcalde ha declarado una crisis humanitaria; pero, aun así, agencias de servicios sociales como la Corporación de Desarrollo Hispano de Detroit, se están preparando para ocuparse de la salud y el bienestar de los inmigrantes una vez que lleguen.

Angie Reyes, directora ejecutiva de DHDC, comentó que su equipo notó que los inmigrantes empezaron a llegar lentamente a finales del año pasado, antes de una gran afluencia en la temporada navideña, en la que vino Carmen. Reyes comparte, que DHDC ha ayudado a unas 200 personas.

“Estamos tratando de conectar (a los inmigrantes) con recursos, conseguirles ropa, pañales y artículos de primera necesidad”.

Mary Carmen Muñoz, directora ejecutiva de Latin Americans for Social and Economic Development (LA-SED), mencionó que su organización, la cual también trabaja con inmigrantes y refugiados, ha visto un aumento significativo de venezolanos y muchos de ellos son familias sin ropa para el invierno.

“El medio ambiente los desafía”, dijo Muñoz. “Brindamos ayuda inmediata y trabajamos con Freedom House (hogar temporal para solicitantes de asilo de todo el mundo) para ayudarlos a encontrar vivienda”.

No encontró ningún lugar seguro

El viaje de Carmen a Detroit tuvo muchas paradas.

Después de dejar su casa, Carmen probó suerte en su vecina Colombia, que alberga la comunidad de refugiados venezolanos más grande del mundo.

Llegó solo con una mochila, como parte de una multitud de refugiados. Evitó a los estafadores que se aprovechan de los recién llegados asustados, caminó y pidió “aventones” hasta que llegó a Barbosa, una pequeña ciudad en las afueras de Medellín, la segunda ciudad más grande de Colombia, y trató de establecerse.

Carmen consiguió trabajo de cocinera, en un pequeño restaurante, donde la trataron con calidez y respeto, pero el salario era tan bajo que apenas podía reunir el dinero para pagar el hospedaje en el que se quedaba; a pesar de trabajar siete días a la semana. Después de tres meses, todavía no tenía suficiente para comida ni nada, por lo que sintió que no tenía más remedio que continuar.

Una tía que vivía en Ecuador la invitó a quedarse hasta que se recuperara. Desplazada por segunda vez, caminó kilómetros, tomó autobuses y pidió “aventones” hasta Quito, la capital de Ecuador, donde empezaría de nuevo y trataría de salir adelante.

Durante cinco años funcionó. Carmen se apresuraba: cocinaba y vendía arepas en las concurridas calles durante el día y con una hielera les vendía helados a los carros que pasaban por la noche. Ganaba lo suficiente para alquilar una habitación y todavía le quedaba dinero para hacer la compra. Había vida en Ecuador. En el 2020, ella encontró una pareja que la hacía feliz y en 2021 dio a luz a una hija, quizás finalmente había llegado a su destino, pensó.

Pero a su alrededor comenzaron a aparecer signos de una inestabilidad cada vez mayor. Una presencia creciente de narcotraficantes y cárteles internacionales de México y Albania establecieron rutas en Ecuador. Trajeron consigo una violencia aterradora, dejando a Carmen en una constante de inquietud. Veía que las cosas iban cada vez peor en Ecuador.

Las cosas continúan mal en Ecuador. Más de un año y medio después de su partida, hombres armados irrumpieron en el estudio de una importante estación de televisión ecuatoriana, durante una transmisión en vivo. El ataque se produjo después de una serie de episodios violentos que se extendieron por todo el país, incluidas explosiones y secuestro de policías.

En agosto de 2022, Carmen decidió desarraigar nuevamente su vida; poniendo su mirada en Estados Unidos. “Cualquier otro país iba a ser más de lo mismo…más de apenas, sobrevivir…Quería algo mejor”. Comentó.

Su desesperación por no encontrar una vida mejor cerca de casa no era infundada. Según el Banco Mundial, América Latina y el Caribe tienen la “distinción indeseable” de ser una de las regiones más violentas del mundo.

Pero para las personas con poco o nada de dinero, el trayecto hasta la frontera con Estados Unidos es una tortura. Cruzan ocho países y soportan semanas, a veces meses, de viajes peligrosos para llegar a la frontera de México y Estados Unidos. Los migrantes se enfrentan a terrenos peligrosos, expuestos a enfermedades y violencia a manos de grupos criminales.

Una y otra vez, le advirtieron a Carmen sobre el despiadado camino, pero ella estaba decidida a hacer de este movimiento, el último. Con su bebé de diez meses a cuestas y embarazada de cuatro meses, ella cruzaría el Tapón del Darién, un peligroso tramo de jungla de 66 millas que conecta Colombia y Panamá y marca el comienzo del traicionero viaje hacia el norte, que tomaría dos meses.

“La selva es un negocio… la gente te exprime, pidiéndote dinero tan pronto como llegas allí. No hay final para ello; en cada momento, alguien está ahí para extorsionarte”, expresó Carmen.

Un viaje traicionero

Carmen vivía con el temor constante de ser violada, secuestrada o asesinada, pero siguió caminando a través de una densa selva tropical que cubría montañas escarpadas y vastos pantanos. Pasó junto a montones de equipaje, ropa y mochilas dejadas por los migrantes que se dieron cuenta de que ya no podían cargar sus pertenencias. Pasando hombres armados y cadáveres.

“Agarré una sábana que estaba en el suelo para envolver a mi hija porque tenía fiebre… pero cuando saqué la sábana, debajo había un niño muerto de unos tres o cuatro años. Verlo me llenó de horror y pánico”, dijo.

Finalmente llegó a Panamá, pero tuvo que seguir caminando, cruzando ríos y arroyos. En un cruce, perdió el control y fue arrastrada por la fuerte corriente del río.

Llevaba a su bebé en brazos, pero cuando el agua la alejó de su grupo de aproximadamente 50 personas, sintió que alguien agarraba a la bebé; soltó a su hija y dejó que el agua se la llevara.

“Preferí dejar ir a mi hija para salvarla. Si no la hubiera soltado, me la hubiera llevado conmigo y se hubiera ahogado”, dijo Carmen.

El río la jaló y la arrojó contra las rocas. Comenzó a tragar agua y sintió que se ahogaba. Entonces, unas manos fuertes la agarraron. Ella dice que un hombre que sabía nadar regresó para salvarla.

A su hija, que ahora tiene dos años, le da miedo el agua. “A veces grita cuando la baño, dígame, ¿qué niño grita al bañarse?” preguntó.

El resto de su viaje fue igual de dramático. Caminó y pidió ride por el resto de Panamá, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras y Guatemala, cargando a su hija durante todo el camino. Cada día había una nueva lucha, pero ella seguía caminando.

México, un país plagado de cárteles, policías corruptos y traficantes de personas deseosos de sacar provecho del flujo de personas que se dirigen al norte, estaba por delante. A medida que avanzaba, se aterrorizaba de que la asesinaran, secuestraran o extorsionaran, situaciones frecuentes para personas como ella en México, donde las estafas por protección migratoria son una industria de miles de millones de dólares.

Elizabeth Orozco Vásquez, directora ejecutiva de Freedom House Detroit, comentó “estas no son historias únicas”.

“Hemos escuchado de todo. Cruzan la selva donde hay cadáveres. Los hombres suelen hacer el viaje más rápido, pero las mujeres y los niños tardan más porque tienen que esconderse por la noche por miedo a que los violen. En todo el camino hasta la frontera norte la gente está siendo explotada”, dijo Orozco Vásquez. “Tuvimos a una mujer que vino con dos niños. Fue violada en México. Tenía siete meses de embarazo cuando llegó a Freedom House”.

Orozco Vásquez añade que “nadie haría ese tipo de viaje si su patria estuviera segura. Esta gente realmente no puede regresar, sus países se han derrumbado, es demasiado peligroso”.

Dos meses después de salir de Ecuador, desnutrida, deshidratada y ahora con seis meses de embarazo, Carmen llegó a Ciudad Juárez, donde al otro lado del Río Grande estaba El Paso, Texas. Cruzó ese último río y se entregó a los agentes de la Patrulla Fronteriza.

Cuando la policía la detuvo, lloró de alegría. “Me invadió una sensación de paz cuando llegué a los Estados Unidos…me sentí segura”.

Las dificultades continúan

En octubre de 2022, Carmen pasó nueve días en un centro de procesamiento y detención de inmigrantes, que ella describe como una “prisión”. Luego, una organización católica le compró un boleto de autobús a la ciudad de Nueva York, donde se unió a más de 150.000 recién llegados, una avalancha de inmigrantes que ha sobrecargado los servicios de la ciudad.

Carmen ingresó a un hotel de Manhattan, convertido en alojamiento de emergencia para inmigrantes y unos meses después de llegar, dio a luz a su hijo en un hospital de la ciudad de Nueva York. Se sentía esperanzada por su nueva vida.

Pero no duró mucho. Poco después del nacimiento de su bebé, su salud mental comenzó a deteriorarse. “Me dijeron que tenía depresión posparto”, dijo ella.

Durante meses, Carmen se aisló en su cuarto de hotel. No podía trabajar y luchaba por hacer amigos. A veces, paseaba hasta el vestíbulo del hotel remodelado, una plaza, donde migrantes y refugiados se reunían diariamente. Fue allí varias veces para intentar conocer gente, pero estallaron peleas que la asustaron.

“Lloraba todo el tiempo… si alguien me decía algo, comenzaba a llorar”.

A medida que pasaban las semanas, Carmen comenzó a cortarse. Estaba consumida por la depresión. Después de casi un año en esa habitación de hotel, no pudo soportarlo más. A finales de octubre de 2023, llevó a sus hijos de regreso a la Autoridad Portuaria de Nueva York y abordó un autobús, dejando atrás una vez más su hogar adoptivo. Esta vez se dirigía a Detroit, donde su hermano se había mudado y la había invitado a unirse a él.

La ciudad de Detroit compartió, que no hay datos sobre el número total de inmigrantes que han llegado. Sin embargo, David M. Bowser, jefe de soluciones de vivienda y servicios de apoyo de la ciudad, dijo que actualmente hay 144 recién llegados, que ocupan camas en instalaciones de emergencia.

“La ciudad continúa trabajando estrechamente con los socios locales, para conocer y abordar las necesidades de todos los residentes, ya sean nuevos o antiguos de la ciudad de Detroit”, dijo Bowser.

Cuando llegó Carmen encontró más desafíos, pero también un nuevo hogar. Recientemente consiguió un pequeño apartamento de una habitación, donde vive con su pareja, sus dos hijos y su hermana.

“Sufrí todos los días del viaje, dormí en las calles, me trataron muy mal, tenía mucha hambre y la salud de mi hija se resintió. Nunca lo hubiera hecho si hubiera sabido como iba a ser”, expresó Carmen.

Desde su ataque de pánico en Vernor Hwy en el suroeste de Detroit, Carmen comenzó la escuela, aprendió a leer y se está adaptando a su nuevo hogar.

“Por primera vez en mi vida siento que estoy dando un paso por delante,” afirmó.

Recursos para inmigrantes en Detroit

Servicios sociales

LA-SED: Latin Americans for Social and Economic Development

4138 Vernor Hwy,

Detroit, MI 48209

313-554-2025

Ayuda mutua

Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation

1211 Trumbull, Detroit 48126

313-967-4880

Church of the Messiah

231 E Grand Blvd,

Detroit, MI 48207

313-567-1158

Servicios Legales

Southwest Detroit Immigrant

and Refugee Center

17375 Harper Ave, Suite 24124

Detroit, MI 48224

313-288-9904

Alojamiento

Freedom House Detroit

1777 N Rademacher St,

Detroit, MI 48209

313-964-4320

City of Detroit’s Housing & Revitalization Department

Coleman A. Young Municipal Center, 2 Woodward Ave. – Suite 908, Detroit, MI 48226

(313) 224-6380

Traducción por Carmen Elena Luna.