Modern technology is supporting a new movement to unravel an abundance of fascinating stories about Detroit natives from the Filipino, African diaspora, and Latino communities.

The Detroit Narrative Agency (DNA), a community organization that disrupts harmful narratives about Detroit, is providing the opportunity to filmmakers from Detroit to tell real Detroit stories. A handful of “Detroit narrative-shifters” as the agency refers to the storytellers were chosen to bring social justice to the city by changing the way communities in Detroit are represented.

Alicia Diaz, one of the chosen Detroit narrative-shifters and a part-time professor at Wayne State University, chose to tell the story of the Latino refugee and immigrant population that has been in Detroit since the 1980s. Diaz depicts their battle to escape violence and poverty, live out their dreams, and create a safe space for other refugees and immigrants.

With a grant from DNA, her first short film, Dangerous Times: Rebellious Response, Diaz follows the lives of Detroit refugee and immigrant activist Esther Galvez, who was a part of the Sanctuary Movement, a religious and political movement that created a safe haven for Central American refugees in the 1980s.

Through Galvez, Diaz met the subjects of her film such as Shianouk Mariona.

“What always struck me was that she very much wanted the stories of the women, men and children with whom she worked to be told – not hers. The stories of terror, of courage, of survival, of making decisions no one envisions making yet having to do so; the struggles to feel fully human once more and be heard in their own voices.”

Mariona whose family was amongst the most visible Salvadorian exiles in the U.S because, “they chose to confront the nation that had funded billions of dollars to El Salvador bringing with it incalculable misery” said Diaz

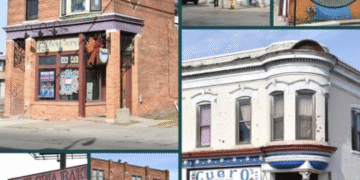

In addition to following Galvez and Mariona, Diaz includes in the documentary the long history of Latinos in Southwest Detroit.

“The real thing behind the documentary is about Latinx people crafting our own narratives,” Diaz proclaimed passionately. “Often when people think of Detroit they rarely ever think about the Latinx people that have lived here for 100 years because our stories are not front and center like stories of other communities.”

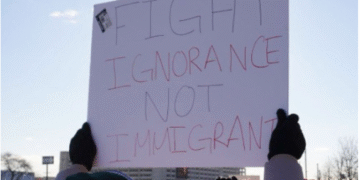

Diaz opened her lens to the community’s current issues under the Trump administration by following other young Detroit activists fighting for the rights of the undocumented and for recipients of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, or DACA.

“It’s a complex and rich story of a community that is evolving and has spread way beyond the physical boundaries of what is known as Mexicantown or Southwest,” Diaz said. “We are Detroiters too! It’s important when you look at a city ‘whose eyes are you seeing it through,’ and that was my motivation for this film.”

Diaz didn’t always see herself as a filmmaker; 15 years ago, if someone told her that she would be in the position she is now, she would have laughed, she said. It was Diaz’s childhood dream to become a writer; as a child, she spent her free time writing fictional stories.

As she got older, she continued strengthening her writing skills while working on her knowledge of the sciences. At the time that she graduated from high school in the 70s, diversity movements in STEM fields were in their beginning stages. However, Diaz was determined to get her undergraduate degree in engineering because she doubted that she would find a career in writing.

Diaz never went through with becoming an engineer. She says she was discouraged when she got to college. She also had no real support system around her to push her to continue because there were no other women of color in the field.

To this day, she does not regret never getting her engineering degree because it influenced her decision to major in political science and economics and to eventually pursue a law degree.

Diaz took the traditional route in her first 20 years of being a lawyer. She became a judicial law clerk for one of the justices of the Michigan State Supreme Court and gained a lot of success in her career but grew increasingly unhappy.

“I think things started to change when I started to interview at other firms that did more civil rights work,” chuckled Diaz, “Then I decided to volunteer for a mayoral campaign for former Supreme Court Justice Dennis Archer, and my former boss, which led me to look at the city very differently.”

The campaign opened her eyes to the amount of suffering Detroit was experiencing then, and it made her realize how most people turned a blind eye to suffering. People tended only to enjoy the few successful parts of Detroit.

This eye-opening experience led her to do economic development work for the city. After working for a few economic development businesses, she had the bright idea of starting her own company from the ground up to support city investments.

A decade into it, her small company grew more successful. However, her new career path came to a halt when the U.S. government investigated her business partner under the same investigation of former Detroit Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick. In the investigation, the government found that her partner had made an investment that did not have the client’s consent, which led to the company’s downfall.

“After that failure, I realized I had a choice: I could either go back and try to rebuild this corporate life, or I could really start to live,” Diaz said. “I decided to put my quality of life first and do something that I really wanted to do, which was to become an instructor and teach the younger generation that their stories matter.

“She is brilliant with lots of life experience, but she doesn’t judge, isn’t condescending, and is an amazing listener,” said Melissa Morse, friend/coworker of Diaz and the assistant director of the Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies (CLLAS) program at WSU.

Now, Diaz works on an ofrenda for DIA’s annual Dia de los Muertos installation with her CLLAS students.

“The Ofrenda focuses on the prices paid and the resistance by Latinx and Latin American ancestors to the silencing of voice, said Diaz”

Diaz continues to teach her students the importance of being honest with their stories, and uses her film to provoke deep conversions about generational trauma.

Andrea Meza works as a social worker at United Community Housing Coalition and is a recent broadcast journalism graduate from Wayne State University. Her main passion is informing and supporting the community.